My previous post on whether long prison sentences work deliberately started with talking about the concentration of crime. It seems to be clear that a small, rotten minority are responsible for a disproportionate amount of crime. Longer incarceration is particularly required for them. The post was clear that longer sentences probably do not deter crime but they do incapacitate.

What about for those criminals not in that rotten, persistent offending minority? In that context, I think its right to challenge whether police are more important than prisons.

You’re not in Kansas anymore: the importance of hot spot policing

Hot spot policing entails police officers patrolling, or being visible, in high crime areas. It does not require the police to actually arrest, or even stop and search or frisk, any person. (That is not to say that stop and search powers aren’t a crude proxy for hot spot policing, but it’s important to define our terms properly). There are numerous real-world studies and observations about how useful hot spot policing is. This literature was, I think its fair to say, triggered by a contrarian finding from Kansas.

Kelling et al (1974) are responsible for the relatively well known Kansas City Patrol Experiment. They looked at three different scenarios of how police carried out their patrols: un-patrolled, reactive and pro-active. They found that across these different patrolling behaviours, there was no difference in crime in the 15 areas of Kansas they looked at. Carl B Klockars, one of the leading criminologists of the 1980s, was so enthused by these findings that he went as far as saying that “it makes about as much sense to have police patrol routinely in cars to fight crime as it does to have firemen patrol routinely in fire trucks to fight fire.”

The study itself had a number of problems which were highlighted throughout the 1970s. Larson (1975) carried out an analysis which showed that ‘the particular experimental design used in Kansas City resulted in a significant continued patrol presence in the depleted areas’ - in effect, the patrol sizes, the volume and movement of patrols in the ‘reactive’ beats, makes it extremely difficult to trust the findings in relation to the ‘un-patrolled’ beats. For our purposes, its also worth emphasising that the study looked at police beats, not more granular hot spots.

Since the Kansas City Patrol Experiment, there has been a robust, and steady, repudiation of the argument it supported. A couple of notable examples from the 1990s:

Sherman and Weisburd (1995) looked at increases in patrol numbers at 55 of 110 hot spots in Minneapolis (doubling the size of the standard patrol as compared against a control) and found reductions of total crime of between 6% and 13%, with robbery dropping by about 20%.

Sherman and Rogan (1995) looked at crack houses in Jersey: of just over 200 sites with high level of drug activity, only half were raided; those raided had an 8% reduction in police call out rates and crimes in the location (though the effect started to wane over time).

Since the 1990s, this stream of studies undermining the Kansas finding has continued. Looking at the period between 2004 and 2012 in New York, MacDonald et al (2016) study areas designated as ‘impact zones’ (i.e., areas where police were directed as part of Operation Impact). They find significant reductions in crime, particularly of burglary and robbery. Unlike other studies, they also looked at the impact of whether crime is displaced into other areas because of the presence of police. They are able to exclude such displacement in respect of all but one criminal offence.

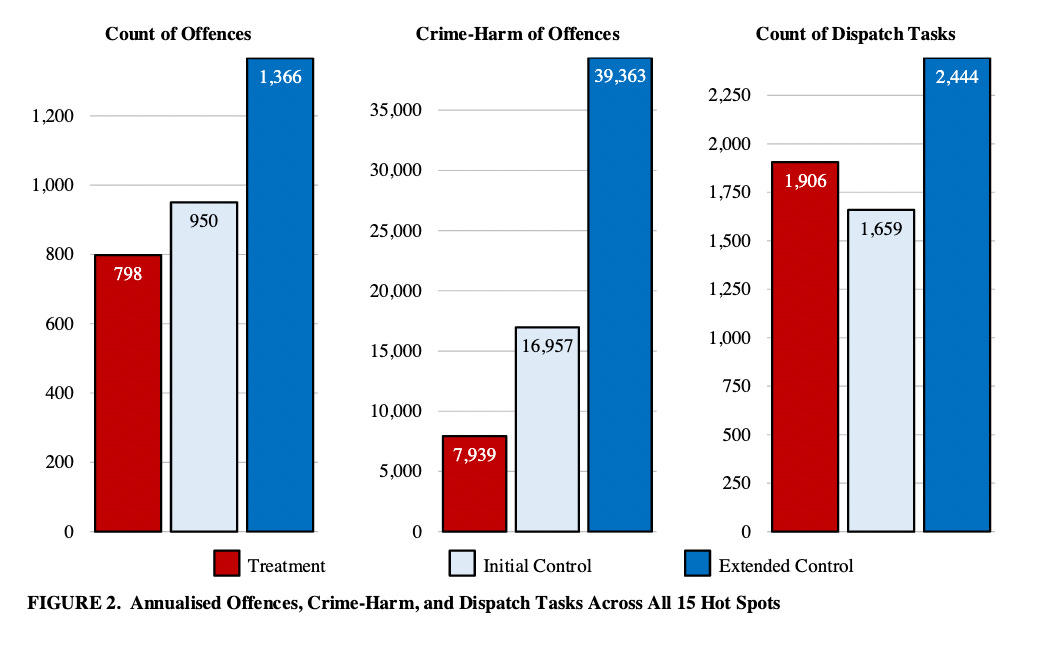

In Australia, Barnes et al (2020) compare not just hot spots subject to intense patrols with control hot spots, but also look at the same hot spots with and without patrols over a long period of time. They find that the average number of reported offences declined by about 20%, and the "crime harm" (which tries to account for the seriousness of the crime) dropped by just over 60% (see Figure 2 above). For those areas which were subject to patrols, and then had the patrols removed, there was a sudden fivefold increase in the crime harm after 4 days.

Here in the UK, we have similarly strong evidence about the impact of hot spot policing:

Fielding and Jones (2012) look at a Manchester trial of hot spot policing, finding reductions of 27% in burglary following implementation.

Ariel et al (2016) look at a hot spot policing programme in Peterborough and found it led to 39 % less reported crimes compared to control conditions, and 20 % reductions in emergency calls-for-service.

Ariel et al (2020) look at a randomised test of hot spots police patrols on platforms of the London Underground. 57 of the 115 highest crime platforms were exposed to foot patrol by officers in 15-minute doses, 4 times per day, during 8-hour shifts on 4 days a week for 6 months, whilst the remaining high crime platforms were not. Ariel et al found that those subject to patrols experienced a reduction in 999 calls by 21%

Bland et al (2021) (in a study entitled “15 minutes per day keeps the violence away”) find that in Cambridge hot spot police patrols led to 44% lower crime harm index scores from serious violence than on control days, as well as 40% fewer incidents across all public crimes against personal victims (with the decline also being found in adjacent areas).

One recent trial in Southend-on-Sea in 2020 found the tactic resulted in a 73.5% drop in violent crime and 31.9% fall in street crime in the 20 highest crime hot spots on days when patrols visited, compared with days they did not.

A hot spot operation by Bedfordshire Police across 21 hot spot neighbourhoods saw harm from serious violence drop by 44% on patrol days.

Just so you know the above isn’t some selective cherry picking of data, there are two systematic reviews / meta-analysis I am aware of:

Brega et al (2019) which finds that ‘hot spots policing programs generate statistically significant crime prevention gains and are more likely to be associated with the diffusion of crime control benefits into surrounding areas rather than crime displacement effects.’

Brega and Wiesburd (2022) look at 53 studies representing 60 tests of hot spots policing programs. They find a statistically significant mean effect size favouring hot spots policing in reducing crime outcomes at treatment places relative to control places of approximately 8.1% or 16% depending on the statistical method utilised.

The above findings are also consistent with the wider findings about policing and crime: we need to hire and spend more on police officers. Unlike longer sentences, I think it is fair and reasonable to conclude that hot spot policing exerts a deterrent effect.

Certainty and celerity, not severity

I’ve previously noted Gary Becker’s model that there should be a low probability of punishment, combined with harsh sentences. As I mentioned in that post, I disagree with that view for the same reasons as Alex Tabarrok. The important point here is that certainty may be more important than severity, particularly if we are not talking about the rotten perpetual offenders and wider deterrent effects.

Judge Steve Alm, a Hawaiian judge (now prosecutor), had a problem with criminals getting back on drugs whilst on probation and then almost immediately re-entering the criminal system. This led to the establishment of ‘Hawaii’s Opportunity Probation with Enforcement (HOPE')’. Mark Kleimann writes about how HOPE in his book When Brute Force Fails noting that those on probation are required to check in with officers and carry out drug tests. A failure to show up, or test negatively, would result in a short - but certain - jail sentence (in most cases as little as 1 day).

Hawken and Kleiman (2016) find that the programme worked: there were fewer missed appointments, failed drug tests, re-arrests, and spent less time jail even though HOPE was quicker to send them there. That said, an attempt to replicate the programmes Arkansas, Oregon and Massachusetts does not seem to have had significant findings (though see here a response). Overall, though, other real world evidence and findings broadly support the effects of certain punishment in reducing crime:

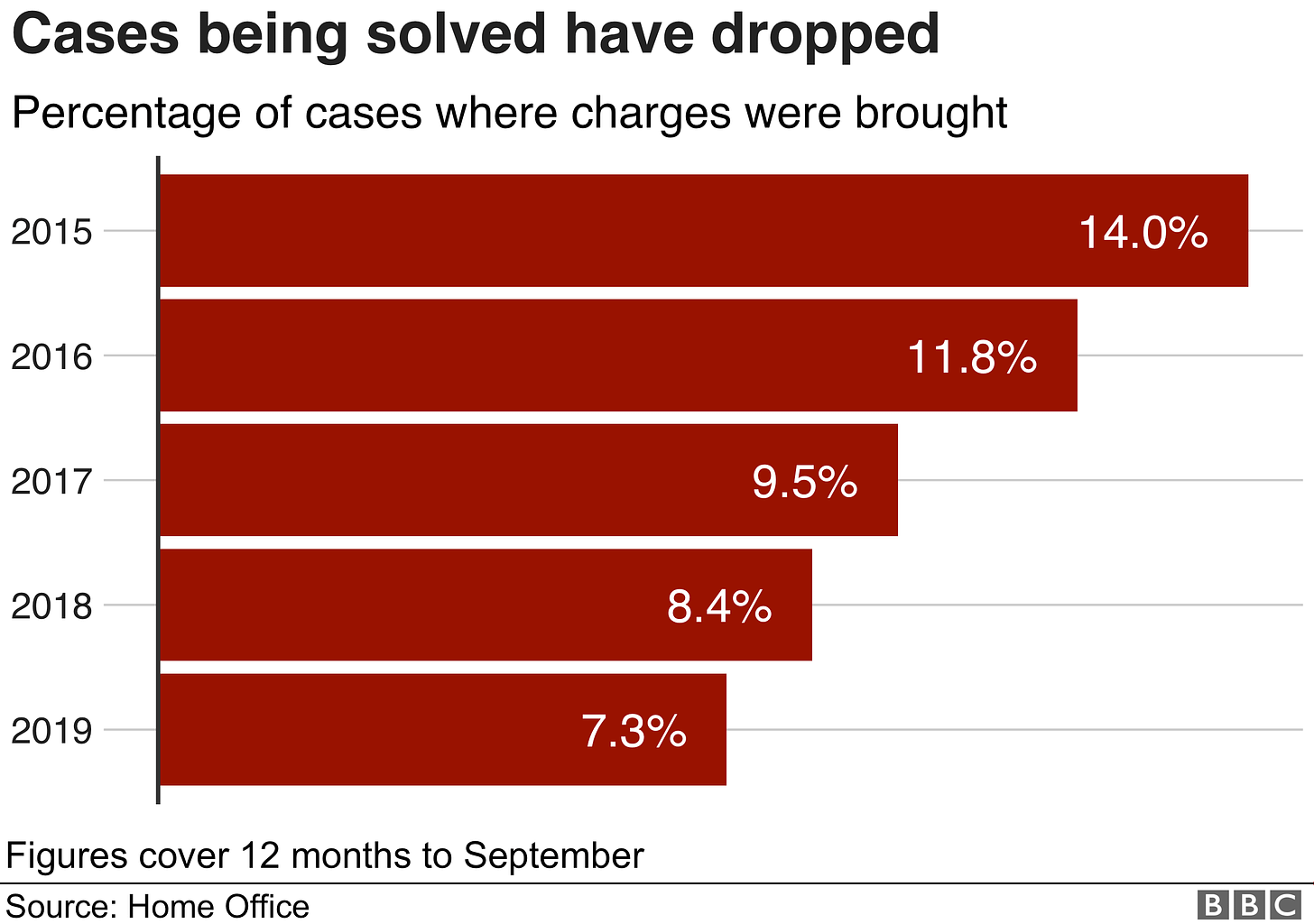

Bandyopadhyay et al (2015) look at the crime data for England and Wales between 1992 and 2007 and find that higher detection rate (i.e., actually apprehending a criminal) reduces crime (though the effect is more limited in high crime areas).

Han et al (2015) similarly find (for England and Wales) that a 1% increase in detection rate leads to 11% decrease in Burglary, a 20% decrease in Theft and Handling and a 14% decrease in Fraud and Forgery.

Bun et al (2020) find similar results in Australia concluding that “criminal activity is highly responsive to the prospect of arrest and conviction, but much less responsive to the prospect or severity of imprisonment”. Their findings include a 1% increase in the probability of arrest for property crimes being associated with a drop in crime rate by 0.283% in the short run and 0.365% in the long run, all other things being equal.

In addition to certainty, there is the question of celerity (i.e., the swiftness) of sanctions. Abramovaite et al (2022) look at celerity and find a mixed bag of results, generally concluding that the impact of a longer wait for a sanction reduces deterrence for property-related crime, but not typically for violent crimes:

For the fixed effects model, the lagged detection rate is statistically significant and consistently negative at the 1% level for theft and burglary but not violence. Lagged sentencing coefficients are significant for theft and burglary (which combined accounts for more than half of total crimes between 1994 to 2008 in England and Wales) and a 1% increase would reduce theft and burglary by 0.22% and 0.15% respectively. Lagged waiting time coefficients are significant and positive for theft, but insignificant for burglary and violence against the person. A 1% increase in waiting time would increase theft by 0.07%.

It’s fair to say that literature is broadly supportive of certain punishments making a difference, but this may not necessarily apply in the same way to all offences. Note in this context that there is also a potential for a connection between hot spot policing and certainty: Rosenfeld et al (2014) find that the certainty of arrests is one of the key mechanisms for hot spot policing reducing some offences, but not others in St Louis.

It’s also worth emphasising that 'certainty’ can be improved post-incarceration: Doleac (2017) compares violent criminals released before and after the date on which their DNA is legally required to be kept on a central record and finds that violent offenders released after are 17% less likely to be incarcerated again within the next 5 years. Anker et al (2017) similarly find that being added to a DNA database reduces recidivism by a statistically-significant 43%. The point here is that the existence of DNA database makes the apprehension of crime more certain.

Porque no los dos?

The belief that longer sentences are required is not incompatible with also wanting to spend more on policing, and also wanting to more certain and swift sentences. The former is probably more important for incapacitating the highly concentrated criminals responsible for a disproportionate amount of crime; the latter is probably more important for general deterrent effects and those who aren’t as impulsive as the aforementioned rotten apples.

The debate about this issue across much of the West is rather dispiriting: we focus on judges and individual, outrageous sentences rather than demanding government legislate the end of automatic releases and increases minimum sentences. There is sometimes a drive to move funds away from policing, toward social programmes, rather than seeing the awful outcomes of police cuts and a Crown Prosecution Service defenestrated. Missing the point means we’re likely to get increases in crime.

In responding to my previous post on longer sentences, Daniel Knowles commented “the real question is does $1 extra spent on prison work better than $1 extra spent on other policies, like detectives, or social programmes?" - I guess my answer is that safety costs so we should spend $2, and the goals of each dollar are non-exchangeable. In other words, those who wish to resist longer sentence, or treat longer sentences as a panacea, are both wrong.