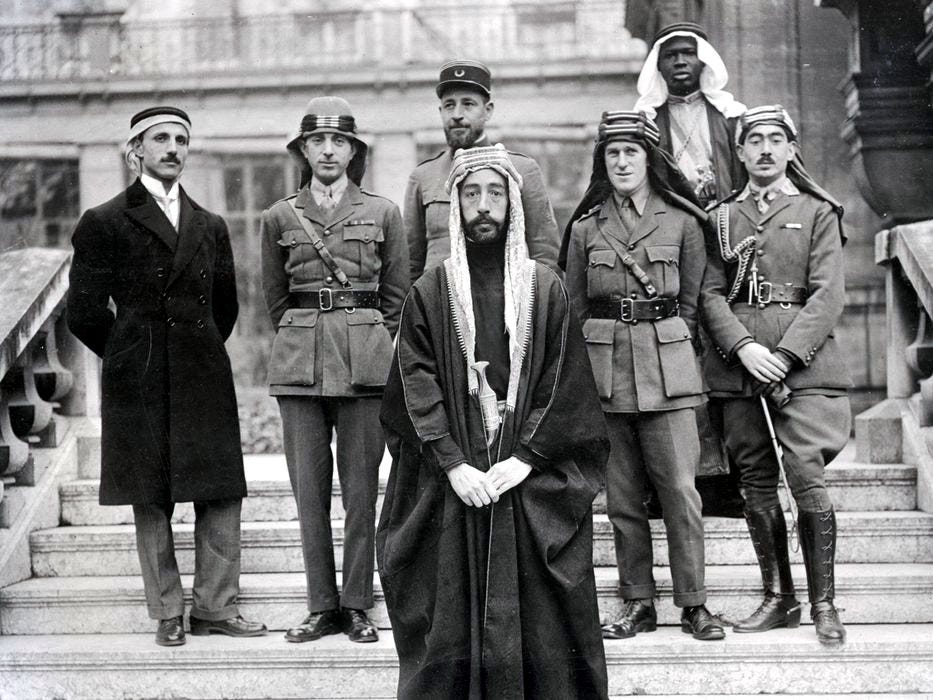

Feysal, future King of Iraq, during the Paris Peace Conference, 1919

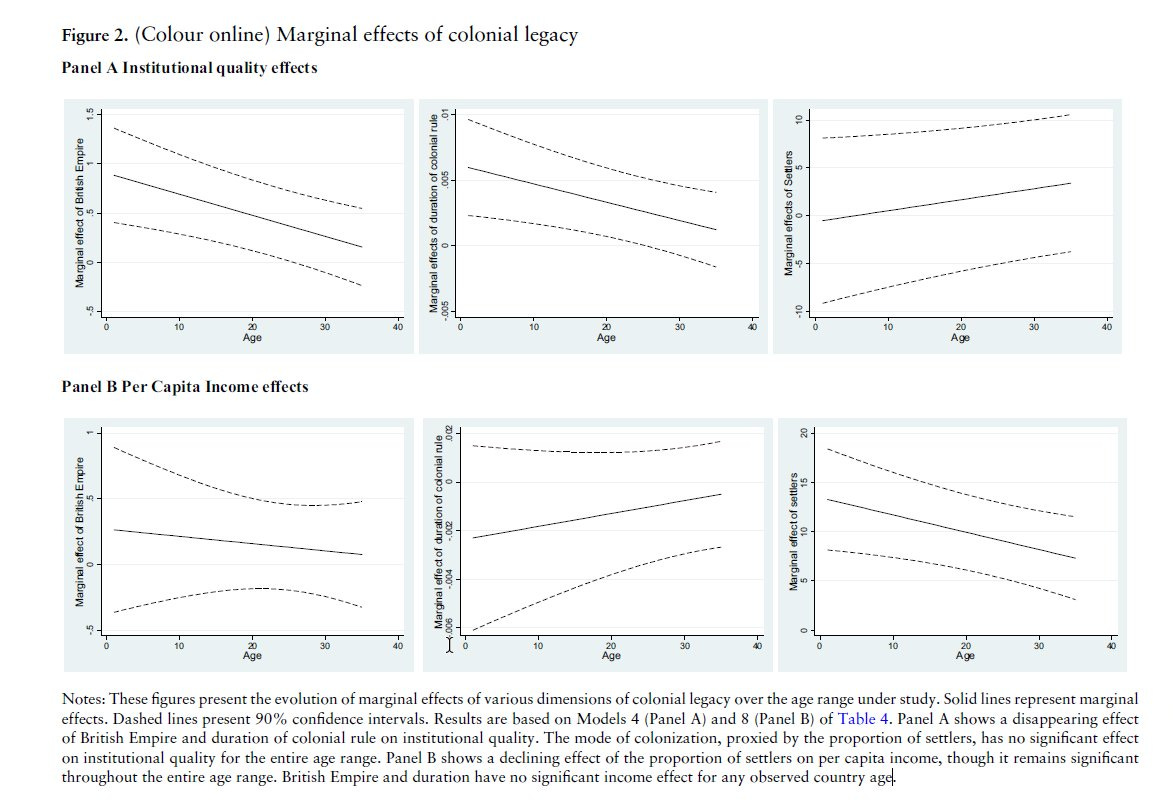

The claim that imperialism has persistent outcomes today is an empirical claim. The gradations of its truth vary depending on the context - for example, it is true that civil law and common law persist in the countries depending on the mother-law of the imperial country. In other contexts, it’s a bit more difficult to make a claim of persistence. For example, Maseland (2017) investigates the claim that colonial history has left an enduring imprint on Africa's institutional and economic development, and finds that there was indeed a negative impact on both institutional quality and economic outcomes but that effect evaporated into non-significance 30-40 years after independence:

The literature in this area is vast. For those interested: studies which directly support positive or neutral findings are here, here, here and here; studies which don’t are here, here and here (see chapter 7 in particular) - in relation to slavery, a useful literature summary is contained in Bertocchi (2015), but note even in that context there are some counterintuitive findings, see Fenske and Kala (2017). The aim of this post is not to delve into that particular issue (though perhaps that will be a post for the future). Instead, I want to focus on a microcosm of this issue: the importance of the Sykes-Picot Agreement to shaping the current borders in the Middle East, and in turn its current stability or lack thereof.

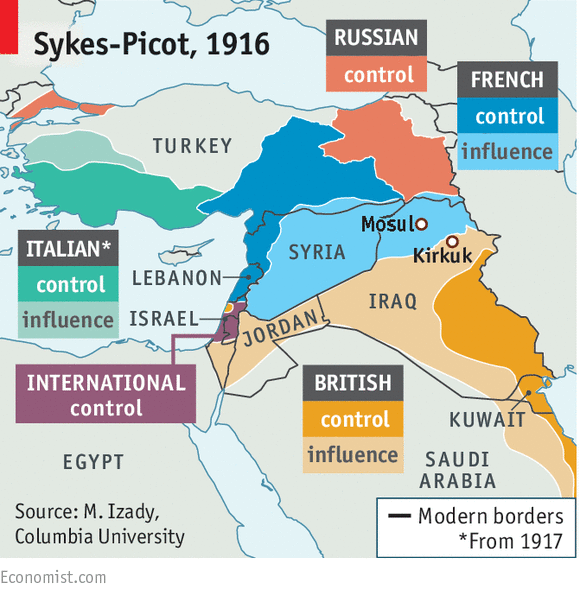

The Sykes-Picot Agreement, a treaty between France and Britain made in 1916, was modified in parts following negotiations with Italy and Russia. The view I take issue with has been espoused by many from popular history books like Fromkin’s A Peace to End All Peace (in which he writes the borders were established by British civil servants), Noam Chomsky (“Sykes-Picot agreement was just an imperial imposition that has no legitimacy; there is no reason for any of these borders—except the interests of the imperial powers”), and even ISIS (see this video entitled “The End of Sykes-Picot” they published).

Does Sykes-Picot look like the Middle East?

The first point is that the primary purpose of the Sykes-Picot Agreement was to deal with the control of coastal connections. It was not intended to create states or set boundaries for states, but instead sought to create zones of influence across the Middle East.

Indeed, when you transpose modern day borders on these zones (as the Economist has above), you barely see a relationship - a fact which, on the face of it, should undermine the primacy of the Sykes-Picot Agreement in explaining modern boundaries. For example, Iraq is comprised of both French and British areas of influence (as well as areas of British areas of “control”); Turkey is comprised of blank areas and both French and Italian areas of influence and control. Various countries do not appear at all (e.g. Kuwait) or modern states are separate even when adjoining areas are within the same area of control (e.g. Syria, Lebanon) or, despite being modern “artificial” states of great significance, are in no zone whatsoever (e.g. Saudi Arabia). There is, of course, no international zone in or around Jerusalem.

Local drivers, demands and elites

But even ignoring the fact that most parts of the agreement were never implemented as the basis for boundaries between nations, the history of the Sykes-Picot Agreement itself should show how it was local drivers, not European machinations, which shaped the contours of the borders of current states. Much is made of Sykes’ infamous proclamation that a border should run ““from the “e” in Acre to the last “k” in Kirkuk” but this quote masks the importance of the existing administrative areas established by the Ottoman Empire. There was no blank canvas; as the historian Reidar Visser puts it:

What is often not realized is the extent to which the agreement merely put on the map patterns of special administrative arrangements that had been in the making under the Ottomans for decades, if not longer. Thus, special Ottoman arrangements for Palestine and Lebanon date back to the nineteenth century: the special administrative district of Lebanon dating to 1861 and the special district of Jerusalem established in the 1870s. As for Iraq, it had been separated entirely from Syria in administrative terms almost since the beginning of Islam – and had for long periods been ruled from Baghdad as a single charge. Again, the only real exception pertains to the Raqqa-Ana borderlands which in brief intervals had gravitated towards Baghdad rather than Damascus. All the talk that these boundaries are a mere hundred years old and that everything was designed by a couple of European colonial strategists is utter unscientific nonsense that collapses immediately upon confrontation with contemporary primary documents, where terms like “Syria” and “Iraq” were in widespread use long before Sykes and Picot even knew where these areas were located

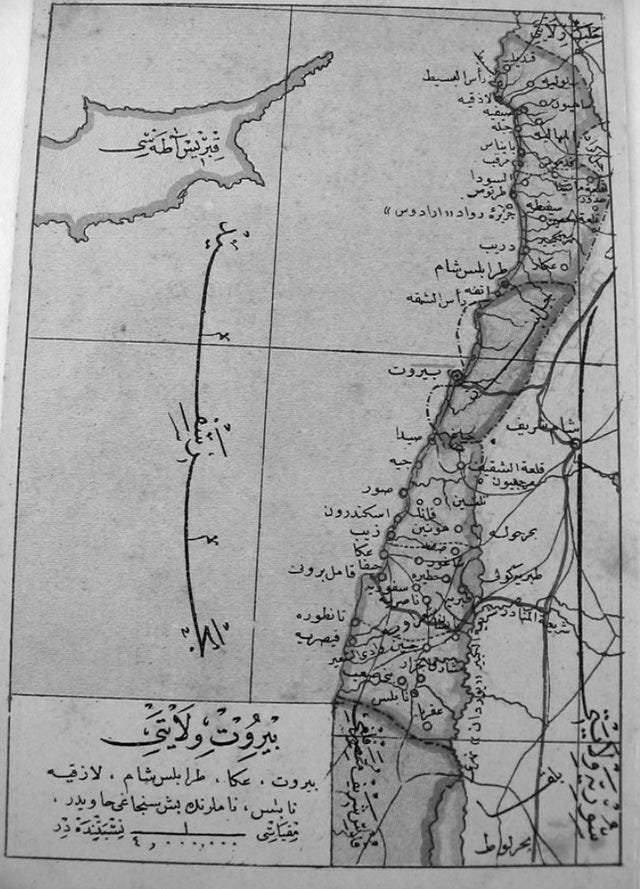

It is these administrative areas, rather than the zones, which are better predictors of modern states. For example, the contours of modern Lebanon are better reflected in the boundaries of the (Ottoman administrative) Vilyaet of Beirut, and the Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate than they are in the vague and unimplemented zones of Sykes-Picot.

Map of Vilyaet of Beirut, 1880-90s

Second, placing primacy on the Sykes-Picot Agreement (or even subsequent treaties like the Treaty of Serves or international conferences like the San Remo conference) gives an unreasonable amount of agency to European powers, and ignores the role of local actors. The history of the Middle East shows that the current day borders were not made in a vacuum, but like virtually every other border is based on wars, competing claims and demands, and negotiations.

Looking at the original map accompanying the Agreement, you can see two areas marked Area A, and Area B. The intention here was to have independent Arab nations which would be friendly to the Britain and France respectively. The reason for this was British support for independent Arab states; a promise they had made in exchange for support from Feysal and Abdullah, the sons of Hussein bin Ali, from the Hashemite dynasty. The focus on Sykes-Picot, then, doesn’t just ignore this history, but the various actions of Arab elites. Let’s consider Iraq in more detail given its the usual candidate for claims of “artificiality”. Here are extracts from Sarah Pursely’s comprehensive article about how the borders of Iraq were set:

… the concept of Iraq and Syria as separate states was widely accepted. It is often forgotten that the San Remo conference, which was held in late April 1920, was in part a hastily convened response by the colonial powers to the Arab conference in Damascus in early March, which had proclaimed the independence of Syria and of Iraq as constitutional monarchies under two different sons of Sharif Husayn, Faysal and Abdallah, respectively. The Iraq declaration was issued by the Iraqi branch of al-Ahd, often referred to as the “Arab nationalist” party. Formed in late 1918 when the original group split into two, al-Ahd al-Iraqi was led by Iraqi ex-Ottoman military officers based in Syria; by 1919 it also had an active branch in Mosul and a less active one in Baghdad. Its official platform called for “the complete independence of Iraq” within “its natural borders”….

What the two parties diverged on was not the demand for an independent Iraqi state stretching from the Persian Gulf to somewhere north of Mosul, distinct from Syria, and with its capital in Baghdad—all of that they agreed on—but rather the question of what kind of foreign assistance the future Iraqi state would rely on. Al-Ahd al-Iraqi’s platform specified that it would rely solely on British assistance, while the platform of Harasstated that independent Iraq could request the assistance of any foreign power it pleased…

There was no map drawn at San Remo in 1920; the agreement explicitly postponed the determination of the borders. But one thing the European powers did at San Remo was ratify the concept of Iraq and Syria as two states, while Sykes-Picot had divided present-day Iraq and Syria into either three or four states. The 1920 agreement was thus more in line with local nationalist demands, and in particular with the recently declared independence of Iraq and Syria, as well as with historical and linguistic understandings in the Arabic-speaking world of Syria and Iraq as geographical areas, and sometimes as states, loosely centered on Damascus and Baghdad, respectively…

Pursley then describes how the the Syria-Iraq border was formed:

In terms of establishing the actual whereabouts of the Iraq-Syria border, the main question… was over the Ottoman province of Dayr al-Zur… In November 1918, conflicts between residents of Dayr al-Zur and the officers of the Arab army in Syria led local notables to appeal directly to Britain to annex the region to the occupied territory of Iraq. British troops duly arrived and did so. But soon the residents became resentful of the British occupation as well, and in 1919, petitioned Damascus for re-incorporation into Syria.

Ironically, it was the Iraqi nationalist officers of al-Ahd al-Iraqi who were ultimately responsible for the inclusion of Dayr al-Zur within Syria. They hoped to use the region as a base for launching attacks from Syria on British occupation forces in Iraq—and that is what they did, thereby helping to spark the 1920 revolt.

Here is Pursley on the Iraq-Saudi border:

In Sykes-Picot, we may recall, the territory envisioned as British-ruled Iraq extended even further south on the eastern side, encompassing the coastline and a good inland chunk of the Arabian Peninsula down to Qatar. The main factor that undid both of these plans, fixing the border in its more northward location, was the military expansion of Abdulaziz ibn Saud of Najd and his Ikhwan forces during these years. In a series of treaties with Abdulaziz from 1920-1927, British officials acknowledged his ongoing territorial conquests by accepting progressive contractions of their envisioned territories. Britain eventually fought to prevent further northward expansion of the Saudi state, launching a massive air offensive into recognized Najdi territory to that end in 1927-1928…

Rather than a line on an empty map, the border was defined in the treaties as a series of lines connecting known waterholes or wells in the desert. The placement of the border on one side or another of each well determined the nationality of the nomadic people living in the borderlands. If a well was placed on the Iraq side, the members of the tribe to which that well was locally understood to belong became Iraqi subjects; otherwise, they became subjects of Najd. The placements themselves were not arbitrary either, since British and Iraqi officials and Abdulaziz all had very strong ideas about which tribes they wanted and did not want as subjects, and negotiated over those that were claimed by both. The tribes also had some say in the matter; a few successfully resisted their new nationality and were transferred to the other side.[

On the Iraq-Turkey border, Pursley writes:

… an important factor in establishing the Iraq-Turkey border, and one that is often forgotten, was the Turkish War of Independence. The history of Turkey’s southern border from 1918-1923 is far too complicated to recount here, but suffice it to say that the Treaty of Sèvres, which was forced on the Ottoman state in August 1920, left Turkey as a small rump state in central Anatolia...This treaty helped fuel the Turkish War of Independence, in which Kemalist forces defeated the Allies and reclaimed much of the land that had been lost since the 1918 armistice, pushing the borders south once again. In this case, the borders were thus imposed on the European powers rather than by them…

The 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which ended the Turkish War of Independence, established most of Turkey’s present-day borders, but not the one with Iraq, since neither Turkey nor Britain would budge on Mosul. The agreement specified that the two parties would attempt a peaceful resolution of the dispute, and if that failed within nine months, the question would be referred to the League of Nations, which it was. After a commission appointed by the league toured Mosul in 1925 to ascertain local opinion, it recommended that the province be given to Iraq. Turkey appealed the decision, but it was upheld and in 1926 Turkey signed the agreement establishing its border with Iraq.

How can anyone read this history and talk of Western imperialism exclusively, or even predominantly, setting the borders of the Middle East? That such local factors are often underplayed at the expense of overstating the importance of two European bureaucrats, also ignores the supervening international context, from the Anglo-French Declaration of November 1918 which seemingly endorsed self-determination across the Middle East, to Woodrow Wilson’s indifference to agreements between Britain and France and push for self-rule. All of this culminated in an open acknowledgment that the terms of the Sykes-Picot Agreement had been superseded:

It constituted an enormous step forward, not so much because the territories that were to be separated from the Ottoman Empire were named, for this had never been a great source of discussion or conflict, but rather because by accepting the mandatory principle and by placing the mandates under the authority and supervision of the League of Nations, some of the provisions of the wartime agreements, particularly the Sykes-Picot Agreement, were automatically superseded. These agreements had called for open annexation of certain areas by France and Britain. Under a mandate system this could not occur (From Paris to Sevres: The Partition of the Ottoman Empire at the Peace Conference 1919-1920, Paul Helmreich).

There is also much to say about what Western plans didn’t come to fruition. Again, to take a popular example: Israel and Palestine. The borders of what the much maligned “international community” would consider Palestine (the West Bank and Gaza) are merely armistice lines established in 1949. They are “arbitrary” with little basis in history: they look little like the British proposal for an Arab state in approximately 70% of the entirety of Yeretz Israel contained in the Peel Commission, nor the UN Partition Plan which allocated an Arab state in just over 50% of the land. The latter were never established despite having the weight of the Western world behind them - a fact almost entirely if not primarily reflective of the Arab elites saying “no” to such proposals. By contrast, the former (i.e., the 1949 armistice lines popularly referred to as the “1967 borders”) were agreed by the Arab states following their own aggressive war against the State of Israel.

Imagined communities

But ignore the fact that Sykes-Picot was fundamentally unimplemented; that borders were predominantly established by local, not international, drivers, demands and elites; that the borders reflected long established administrative areas; that the Agreement was largely superseded by a more accommodating international framework; Noam Chomsky’s view quoted above is that these borders reflect only Western imperialism - do the locals now agree? How is nationhood usually constituted?

It is at least somewhat ironic that those who argue that (European) nationalism is irrationally 'imagined’ would argue that the artificial borders (in the Middle East) do not allow for true self-determination. The underlying assumption is that Middle Eastern states should reflect the ethnic lines and be ethnically homogenous. But leaving this aside, the symbiotic relationship of borders and nationalities is important here. Pursley again notes this this relationship in the context of the Iraqi-Turk disputes over Mosul:

…from 1918 to 1926 Mosul acquired profound significance in the formation of an Iraqi national identity, a process that has received inadequate attention and is thus poorly understood. Already in the 1918-1919 plebiscite, as both Iraqi and British observers noticed at the time, the only unanimous point of agreement was that “Mosul is part of Iraq," and in the coming years nationalist poets in Baghdad and Basra waxed lyrical about Mosul as the “Jewel of Iraq.”

By contrast, consider the Palestinians. Golda Meir (infamously) repeated a talking point of some pro-Israel pundits when she said the Palestinian people “did not exist”. In some ways, Mrs Meir is correct: as the leading Palestinian historian Rashid Khalidi explains in Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness, the modern concept of a “Palestinian” emerged some point in the late 1930s in the aftermath of the Arab revolt, and prior to that, the vast majority of the Arab population from the river to the sea considered themselves south Syrians, or non-specific Arabs.

Nationhood is fluid: Palestinian nationhood descended from Syrian identity in a conclave of the Ottoman Empire but was ignited in the absence of any modern state boundaries, and only after Syria and Jordan were separated from the Mandate for Palestine. It has survived even when the West Bank was annexed to Jordan between 1948 and 1967, and Gaza was militarily occupied by Egypt in the same period. It has thrived notwithstanding the continued Israeli presence in the West Bank and, since the 2005 Israeli disengagement and evacuation of Gaza, Israeli absence in Gaza.

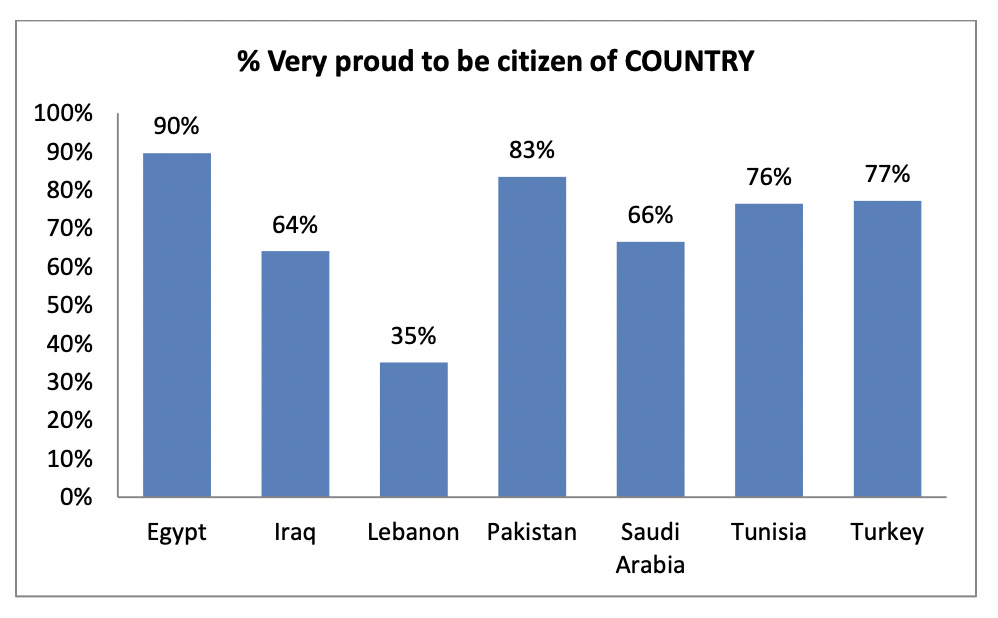

The point is that nationhood sometimes follows the creation of borders themselves and even where it doesn’t, it is incredibly malleable: a relatively modern construct but which has some historical grounding, created in the context of local drivers, competing demands and the ruff and tumble of wars. That nationhood follows such “artificial” drivers does not make the nationhood of those any less real. The following graphs are taken form Moaddel (2013) and show how despite the Middle East’s “artificial” border making, people still have a sense of nationhood:

This isn’t an odd finding, take the work of Alea Robinson (2014) which finds in the context of 14 African nations as follows:

Colonial legacy theories also predict that ethnic group partition is problematic for engendering a common national identity. By contrast, the results show that being a member of a partitioned [by artificial borders] ethnic group is instead positively related to identifying with the territorially defined nation over one’s ethnic group... the legacies touted as impediments to widespread national identification in Africa—ethnic diversity and cultural partition—are, if anything, positively related to national over ethnic identification within African countries.

This isn’t to say borders always produce good results: a post I read over at Broadstreet looks at how the borders of the Weimar Republic are associated with antisemitism (the study design is fairly novel: that authors look at stories of "Kinderschreck”, a bogeyman which had antisemitic undertones; the authors find that “71% of all 1,114 towns reporting Jewish bogeymen are located within 10 kilometers of border crossings, while only 17% of the Weimar population lived within this radius”).

But my view (summarised here) is that the fundamental causes of Middle Eastern authoritarianism and economic backwardness stem from several centuries ago further undermining the explanatory role of borders in the present day institutional framework of the region. But you don’t need to be convinced of that to know what should be very clear from the above: Sykes-Picot is not dead as ISIS claimed, it was never alive - just as we would do well to acknowledge the role of locals in that historic context, we should pay more attention to their current views on nationhood.