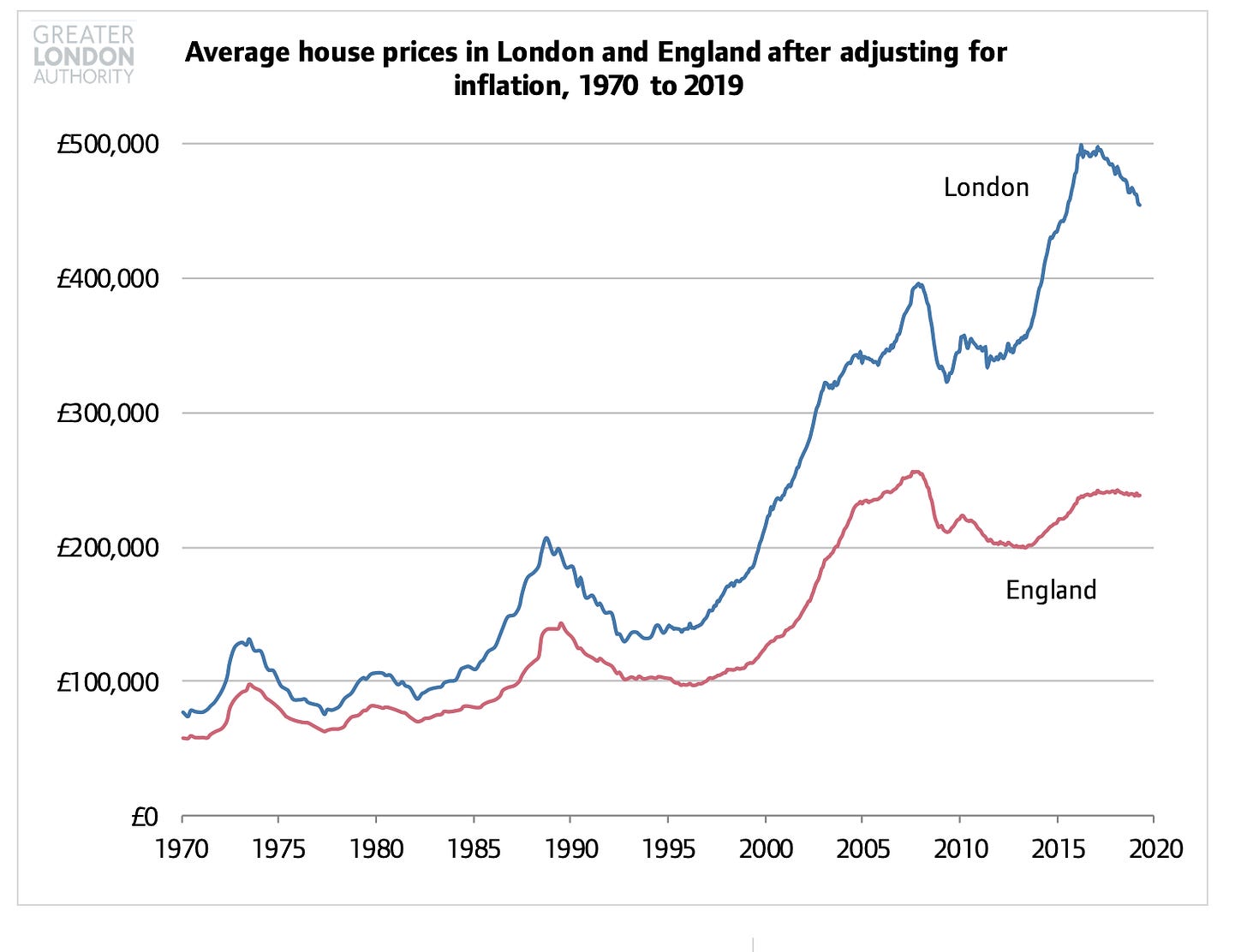

House prices have risen rapidly over the last few decades across the UK. Adjusting for inflation, the average cost of a home in London in 1970 was just over £100,000. It is now somewhere between £450,000 to £500,000.

If you were following a simple supply and demand model, it is natural to think that increasing numbers of immigration to this country have been a partial cause of this increase. But how much exactly? Are there any countervailing factors?

Analysis from the Ministry of Communities and Local Government

MHCLG published analysis in 2018 that looked at the causes of the (average) rise of house prices from 1991 to 2016. The results were that 21% of the rise were attributable to immigration. To put this in context, the rise in incomes was said to have a 150% impact (with new housing supply having an impact of minus 40%). All in all, this works out as £11,000 of the rise between 1991 and 2016 being attributable to immigration which, whilst no insignificant, is relatively small.

How robust is this analysis? One issue with this analysis is that it makes assumptions about the elasticity between household numbers and house prices. The paper itself cautions against using it beyond the 2007 period because of the dated assumptions made. In addition, the paper does not consider or disaggregate (a) immigrant supply of labour in the construction industry, especially in places where build costs are a high fraction of prices; and (b) overall increased incomes per capita, tax revenue and welfare due to high skills immigration (i.e., there is no attempt to assess the relationship between immigration and wider economic metrics). When I spoke to Jonathan Portes about this, he described the paper as “laughable”.

In any event, we should follow literatures, not individual papers.

What does the wider literature say?

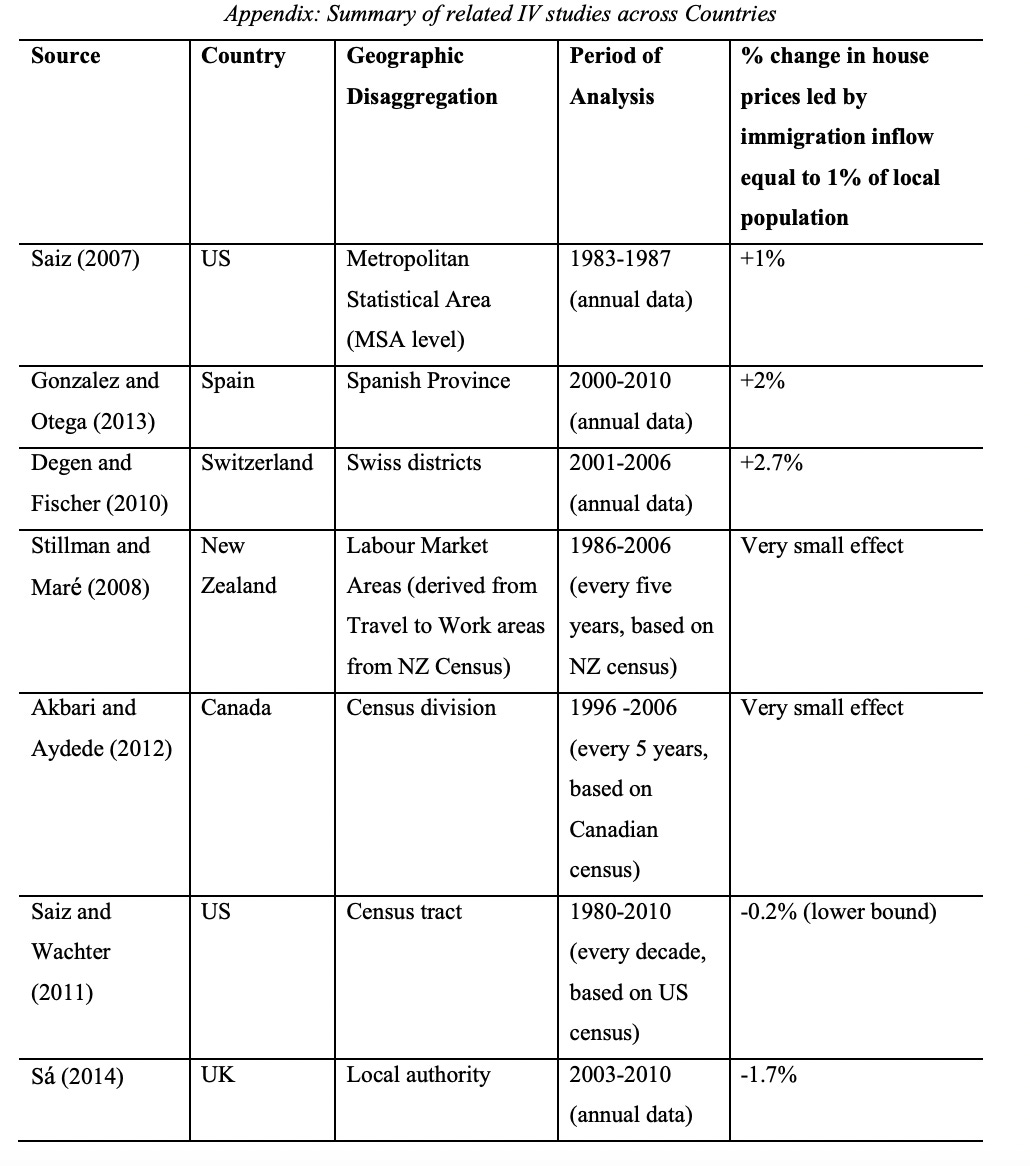

The first point is that MHCLG analysis is very much at the extreme of the literature. Here is a table contained in Zhu et al:

The findings of Zhu et al are also instructive in showing why we need to be much more granular about talking about immigration and housing prices. In particular, their findings are that:

… the reduction in house prices is not statistically significant in low job density areas; however a small but statistically significant negative effect is found in high job density areas; specifically, an increase in the stock of immigrants equal to 1% of the local population is associated with a 0.08% reduction in house prices.

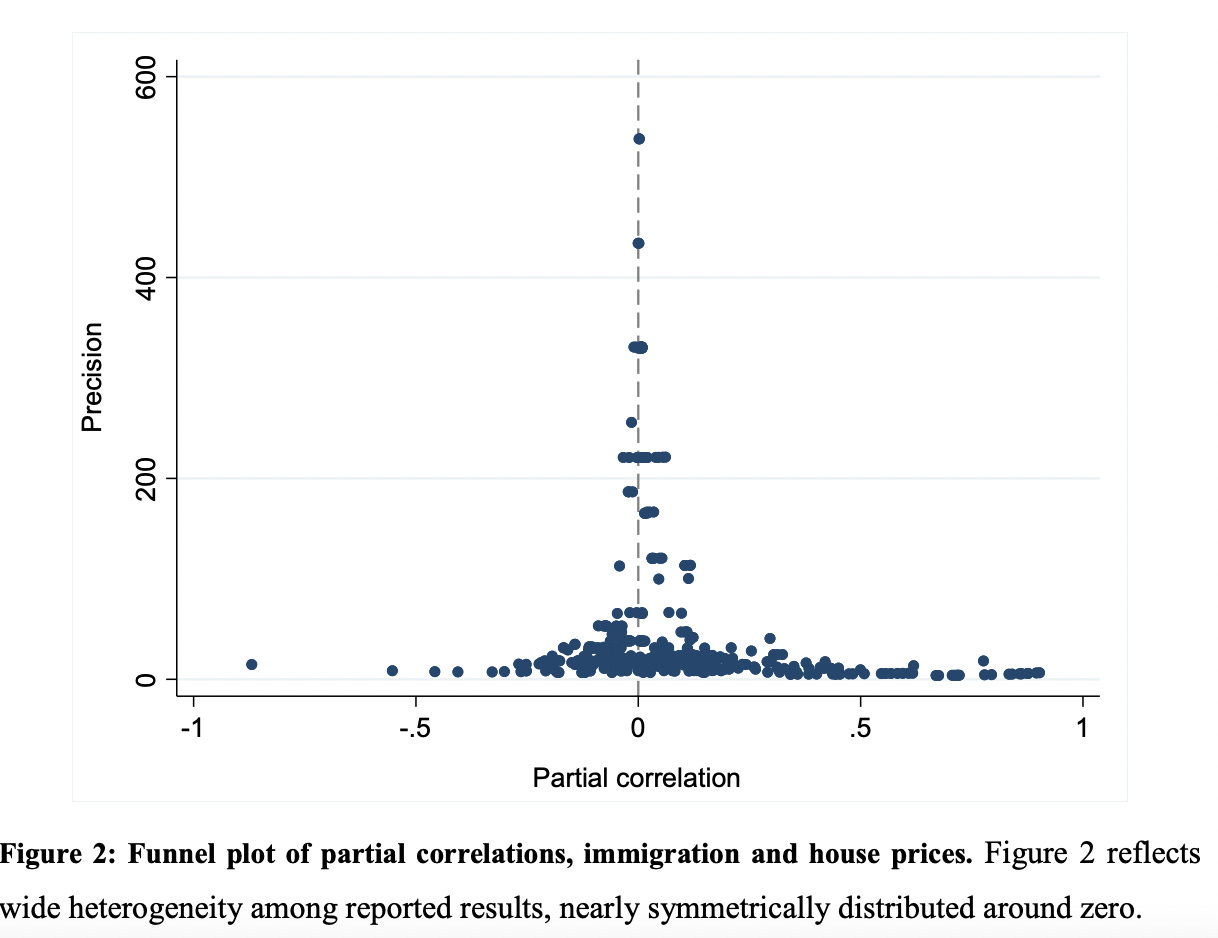

But even Zhu et al shouldn’t be relied upon because its not a systematic literature review. For that, we should look to Larkin et al (2018). They collate 474 estimates of immigration’s impact on house prices in 14 countries. Here is the funnel plot showing the heterogeneity of the dozens of studies they look at:

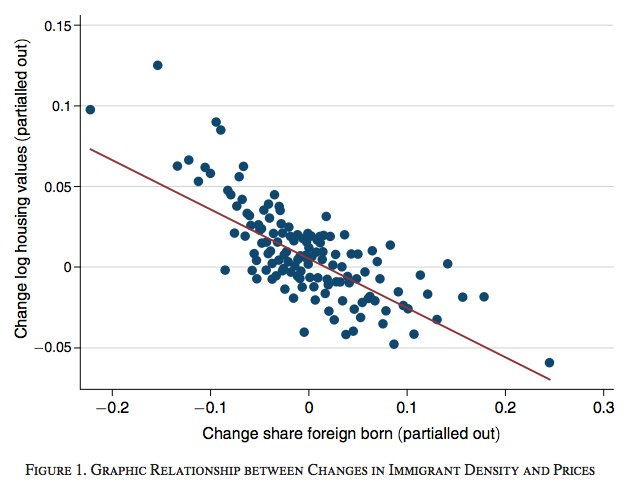

How do we explain all of the range in the literature? One of the key aspects is that it doesn’t account for the moderating effect on nominal adjusted prices of anti-immigrant values. Increasing numbers of immigrants will reduce the value of housing in an area where anti-immigrant attitudes are high. For example, Antoniucci and Marella (2017) show that in Italy, larger immigrant populations coincide with steeper housing price gradients on a national scale - in effect, natives run a mile when immigrants arrive. Similarly, Wachter (2011) in the US finds that there is an association between growing immigrant density and native flight leading to relatively slower housing value appreciation:

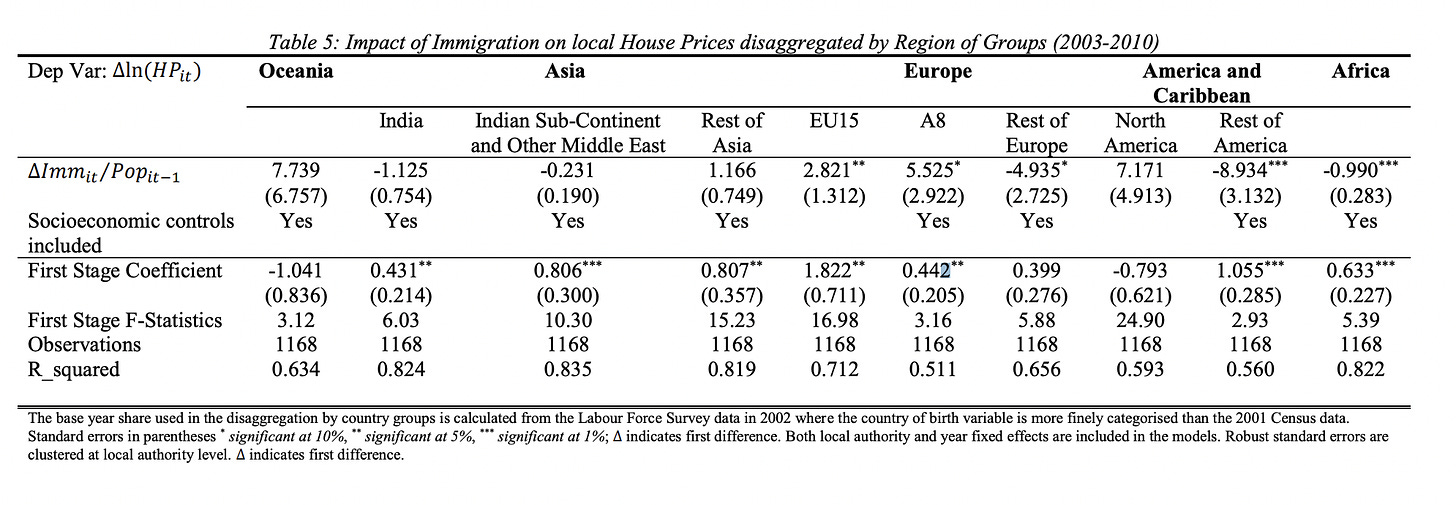

To go back to the meta-analysis (Larkin et al (2018)), they find that a 10pp drop in anti-immigrant attitudes towards immigrants reduces the correlation between immigration and house prices by 0.24. In particular, they find that in the UK there is no significant effect between immigration and house prices, but when they run a counter factual on anti-immigrant attitudes reducing, there is an increase in house prices (see Table 4, Column (3) and (4)). But there’s another element to all this: the composition of immigrants matters. Zhu et al’s study contains this breakdown for the UK:

But, we come back full circle even with these disparate and wide ranging (small) effects, the Migration Observatory summarises the research in this way:

The Migration Advisory Committee study found that the impact of migration on house prices was larger in local authorities with more restrictive planning practices, i.e. those that have higher refusal rates for major developments.

Perspective

It would be tempting if you were anti-immigration to use the MHCLG analysis headline figure of 20%. It would be tempting if you were pro-immigration, to use the findings of non-significance. The truth is that the extent of the impact is too heterogeneous - but even at the most extreme, the impact of immigration on housing is not determinative of the case for immigration. The economic gains from immigration to natives, even ignoring the large utility impacts on immigrants themselves, are moderately large.

In terms of housing policy, some perspective is required: even at the most extreme, we are talking about about the cost of housing being 6.5 times annualised salary as opposed to 7 times salary. Like talking about empty homes, or land banking, or interest rates, talking about immigration in this context distracts from the fundamental issue: the issue with housing is supply. We know, for example, from the work of Hilber and Vermeulen (2014) that “house prices in England would have risen by about 100 percent less, in real terms, from 1974 to 2008 (from £79k to £147k instead of to £226k) if, hypothetically, all regulatory constraints were removed”.

As the inimitable John Myers has been telling us for years: GDP per capita would be 20% higher if we get housing right. These are tangible gains that vastly outweigh the impact of immigrants on housing. We could continue to reap the large economic gains from immigration whilst adding as much as a 0.5 percentage points extra annual GDP growth through a single smart planning reform. Let’s not take our eye off the ball.