The problem

Gary Becker famously proposed a model for deterring crime that coupled low probability apprehension with severe punishment. This, he thought, would be a mechanism which deterred an offender taking into account their risk appetite (see “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach”). For reasons that Alex Tabarrok has explained, the mechanism which Becker’s model relies on doesn’t quite work given criminals lack self-control.

Alex Tabarrok instead argues we should consider criminals as children, and argues:

One thing all recommendations [for parenting] have in common is that the consequences for inappropriate behavior should be be quick, clear, and consistent. Quick responses help not just because children have “high discount rates” (better thought of as difficulty integrating their future selves into a consistent whole but “high discount rates” will do as short hand) but even more importantly because a quick response helps children to understand the relationship between behavior and consequence… Quick, clear and consistent also works in controlling crime. It’s not a coincidence that the same approach works for parenting and crime control because the problems are largely the same.

Alex’s view is that he does not consider severe sentences necessary but instead considers certainty king (i.e., the converse of Becker: high apprehension, low severity). Whilst I think Alex is much more persuasive in developing a theory of how deterrence works relative to Becker, my own view is that the primary purpose of the criminal justice system is not deterrence, retribution or rehabilitation but straight forward incapacitation: paralysing those who do ill for the benefit of the public. As Zimring notes in the Great American Crime Decline, the incapacitation of individuals via imprisonment in the U.S. is responsible for up to 27% of the decline in crime in the U.S. in the 1990s.

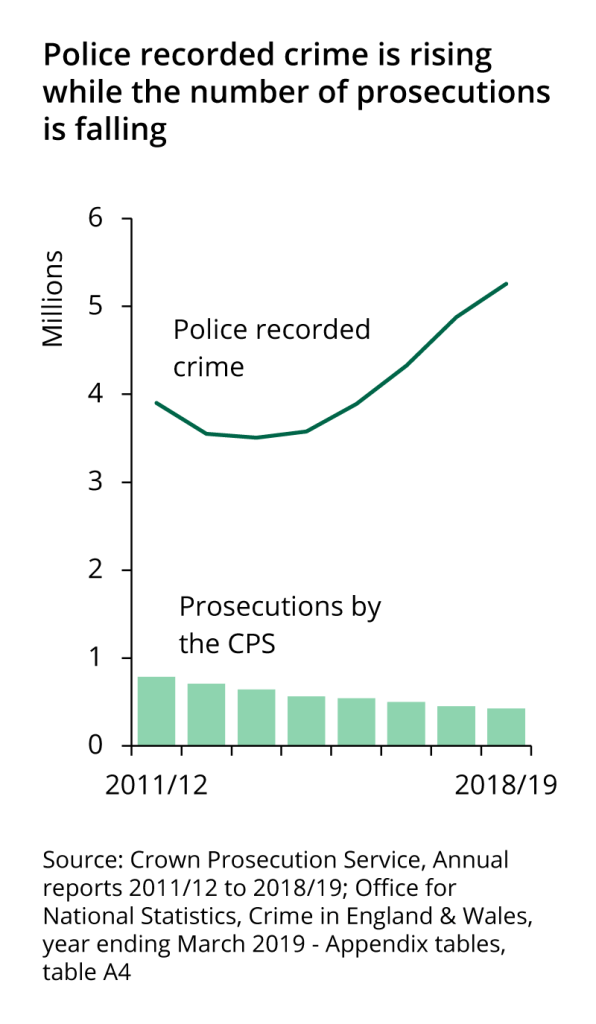

Nonetheless, being ‘quick, clear and consistent’ in punishment works just as well for a model that prioritises incapacitation. For that reason, its important that all aspects of our system work quickly. One area that isn’t as ‘sexy’ as the police is our prosecutorial service. Back in 2012, Policy Exchange published a report by Karen Sosa which looked at how well the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) was doing. The report highlights several troubling statistics:

Excluding guilty pleas, the CPS had successful outcomes in only 60%

of its Magistrates’ Court cases and in fewer than one-third of its Crown

Court casesThe CPS dropped, or took no further action in 176,097 prosecutions in 2011/12 – including 87,992 pre-charge decisions and 88,105 post-charge prosecutions

In 2011/12, a total of 35,494 prosecutions were unsuccessful because the CPS offered no evidence.

Nearly one in ten (10,543) Crown Court cases resulted in no evidence offered.

Nearly one-third of ineffective trials (30%) were the result of the prosecution not being ready or a prosecution witness being absent

Just to emphasise: over 35,000 cases were prosecuted where the CPS ended up offering no evidence. These aren’t weak cases, they are instances where no case is offered. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism has also reported that in a single year there were 45 homicide trials that failed because the CPS provided insufficient or no evidence after a not guilty plea. The ‘headline’ conviction rate which you can see in CPS quarterly reports is usually ~85%, but that figure includes those who plead guilty. This poor record is reflected in other statistics as well:

These failures cost the public purse approximately £21million according to the National Audit Office - but that financial cost is relatively small fry compared to the potential damage to public safety and the effective operation of the criminal justice system: the CPS is wasting the precious time of our courts and police, or worse yet prosecuting innocents, or scuppering the chances of incapacitating the guilty. Despite these failures, no Chief Crown Prosecutor has ever been removed from their office since the CPS was established in 1986.

The causes and potential solutions

Central government funding

The CPS’s funding has been cut quite significantly in the last decade: in 2019, Geoffrey Cox (who was then the Attorney General) noted that they had suffered a 30% cut in funding. This has had a knock on effect on staff numbers: in 2018/19, there were 5,684 full-time equivalent CPS staff in post compared with 8,094 in 2010/11. Amusingly, in 2015, the Sun on Sunday ran an article claiming that CPS prosecutors were running 160 cases at one time. The CPS responded, unironically, saying that the true number was ‘only’ 79 cases at one time.

These cuts, staff reductions and capacity issues have exacerbated the inability to ensure that punishment is ‘quick, clear and consistent’ - indeed the Code for Crown Prosecutors is explicit on this, guiding CPS officials to consider cost to the CPS in making a decision to prosecute:

In considering whether prosecution is proportionate to the likely outcome, the following may be relevant:

i. The cost to the CPS and the wider criminal justice system, especially where it could be regarded as excessive when weighed against any likely penalty. Prosecutors should not decide the public interest on the basis of this factor alone. It is essential that regard is also given to the public interest factors identified… but cost can be a relevant factor when making an overall assessment of the public interest.

In 2019, the government announced a cash injection into the CPS, but that does not reverse the extent of cuts put in place. Reversing these cuts, and the burden on Crown Prosecutors, should be easy for a government intent on making criminals pay, and which has seemingly dropped the mantra of austerity (though its worth noting that even for those, like me, who think austerity’s discontents are overstated, these cuts should have never happened).

Salary

Leaving aside the funding gaps, there is no doubt a relationship between the quality of the CPS and pay: the starting salaries for Crown Prosecutors are £27k, Senior Crown Prosecutors at £42k, and the head of the CPS at £160k. By comparison, at a medium sized law firm, a trainee solicitor can expect £40k, a senior associate can expect in somewhere in the region of £85k to £140k, and its not uncommon for a partner’s take home pay to be in excess of £1million. Just as we should increase the pay of MPs to get better quality MPs - we should increase the pay of those officials who work in the CPS.

Accountability

The Policy Exchange report referenced above has a number of reforms to increase accountability (e.g., involving Police and Crime Commissioners in decisions). I don’t think these reforms are desirable but accountability is an issue: courts are not sanctioning the CPS every time they submit there is no evidence or an egregious insufficiency in the evidence put forward. This may be in part because of courts reluctance to impose costs on the public sector - but this needs to change: courts should admonish the CPS, and the case law which may be a limiting factor in any sanction statutorily overturned via an Act of Parliament.

Interface with the police

The Policy Exchange report notes that there is a blame game between the police and the CPS, both blaming one another for not collating and presenting evidence properly. A survey of Chief Crown Prosecutors found 7 of 11 respondents identified the quality of police files as one of three biggest challenges. I have not been able to find compelling evidence on who should take the largest share of the blame, but in reality points 1 to 3 above should apply just as much to the police, as they do to the CPS.

Myopia

CPS reform is clearly not a panacea; the most effective reform we could undertake at this stage is increasing police funding: some papers suggest hiring an additional 11 police officers is associated with 1 fewer murder, and several studies show increases in raw police numbers are associated with 3-5% reductions in crime. One particular policy to implement is ‘hot spot’ policing. In The City That Became Safe, Zimring finds that hot spot policing to be a statistical “proven success”in reducing homicide in New York. Other studies confirm the same for other crimes in New York. Manchester ran hot-spot policing trials in 2010, Birmingham in 2012 and London in 2012 which all led to decreased levels of violence.

Other debates, however, suffer from failing to acknowledge or account for the issue of CPS reform. For example, there is a long standing debate about whether longer sentences are effective, there are even debates about whether existing criminal offences like damaging public property should be covered by new offences. The failure to confront the failures of the CPS makes these debates myopic, or misunderstood: it is not enough to increase sentence severity without certainty that they will be implemented. The same goes for those who wish to spend their time talking about ‘activist lawyers’ or calling into question the integrity of the judiciary - the reality is the opposite: lawyers should be paid more, and the judiciary given more powers.