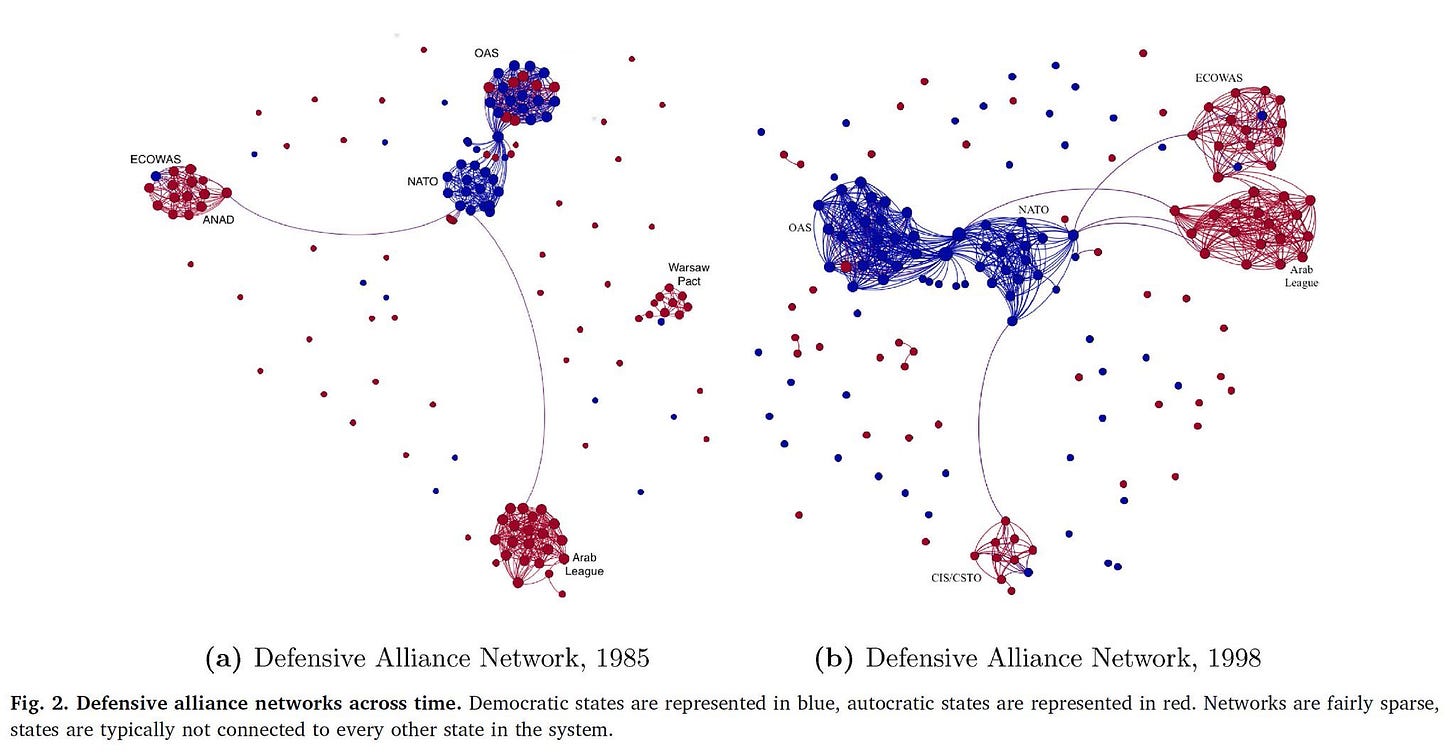

The membership of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) has grown since its inception: Turkey joined in 1952, (West) Germany in 1955, and Spain in 1982 - but it is NATO’s expansion east of the Rhine which gives rise to debate: Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland joined in 1999, followed by a slew of Eastern European countries in 2004. According to various commentators, the expansion to the ‘Bloodlands’ is primarily or solely responsible for Russian aggression, and was a major Western miscalculation. Is that true?

1. Was there a promise not to expand NATO eastwards in the 1990s?

The starting point about any discussion about commitments given to Russia is that there is no agreement, nor public statement, which supports the idea that NATO would not expand. Indeed, Article 10 of the North Atlantic Treaty itself states that “any other European State in a position to further the principles of this Treaty and to contribute to the security of the North Atlantic” can make an application. What is at issue are claims that during negotiations in the 1990s, assurances were provided by U.S. officials to the USSR.

For any of these assurances to carry weight, you have to dubiously presume that statements (note: not legal agreements or treaties) made by U.S. officials could bind successor U.S. administrations, but also sovereign states who willingly chose and wanted to join NATO. But lets continue with that fallacious presumption. So what is the case that these assurances were made? The key statements are those uttered by James Baker to Gorbachev at a meeting during February 1990:

Not once, but three times, Baker tried out the “not one inch eastward” formula with Gorbachev in the February 9, 1990, meeting. He agreed with Gorbachev’s statement in response to the assurances that “NATO expansion is unacceptable.” Baker assured Gorbachev that “neither the President nor I intend to extract any unilateral advantages from the processes that are taking place,” and that the Americans understood that “not only for the Soviet Union but for other European countries as well it is important to have guarantees that if the United States keeps its presence in Germany within the framework of NATO, not an inch of NATO’s present military jurisdiction will spread in an eastern direction.”

Whilst those statements might make it seem like an open and shut case, the context here needs to made clearer. These comments were made in the context of discussions about German reunification; the ‘expansion’ in question here is not about Eastern Europe, it is about NATO presence in reunified Germany, i.e. Eastern Germany. This context is made clear in the records of the discussions kept by Dennis Ross (“we believe that the consultations and discussions in the framework of the ‘24’ mechanism must give a guarantee that the unification of Germany does not lead to the extension of NATO’s military organization to the East.” - the ‘East’ in question being East Germany). Commitments relating to Germany were then negotiated and finalised in the Final Settlement.

This isn’t conjecture - it formed part of the very particular contemporaneous context of the Germany reunification discussions, including in public. Genscher, West Germany’s Foreign Secretary, gave a speech declaring that a united Germany would be a member of NATO, but that NATO’s jurisdiction would not extend to the eastern part prior to the Baker-Gorbachev meeting. As Mark Kramer explains, this is also found in Baker’s notes as well:

Baker quoted Gorbachev’s response, including his statement that ‘‘certainly any extension of the zone of NATO would be unacceptable.’’ Baker then indicated, in parentheses, the inference he would draw from Gorbachev’s comments: ‘‘By implication, NATO in its current zone might be acceptable.’’

That addition in parentheses makes it clear that these are all statements about the presence of forces in West Germany. There was no “cascade of assurances” as alleged by the National Security Archive - and we know this because of what the players involved in these discussions say themselves. You might expect James Baker to confirm that there was “never, never” an assurance provided, and you wont be surprised that attempts to dictate NATO presence were resisted by then President Bush (“To hell with that”) but it is also confirmed by Mikhail Gorbachev:

RBTH: One of the key issues that has arisen in connection with the events in Ukraine is NATO expansion into the East. Do you get the feeling that your Western partners lied to you when they were developing their future plans in Eastern Europe? Why didn’t you insist that the promises made to you – particularly U.S. Secretary of State James Baker’s promise that NATO would not expand into the East – be legally encoded? I will quote Baker: “NATO will not move one inch further east.”

M.G.: The topic of “NATO expansion” was not discussed at all, and it wasn’t brought up in those years. I say this with full responsibility. Not a singe Eastern European country raised the issue, not even after the Warsaw Pact ceased to exist in 1991. Western leaders didn’t bring it up, either. Another issue we brought up was discussed: making sure that NATO’s military structures would not advance and that additional armed forces from the alliance would not be deployed on the territory of the then-GDR after German reunification. Baker’s statement, mentioned in your question, was made in that context. Kohl and [German Vice Chancellor Hans-Dietrich] Genscher talked about it.

Third hand or second hand reports on this issue do not change what the people said in the room where it happened. When you hear, therefore, that assurances were given by Russia apologists - don’t believe it; they are using statements made in a very specific context about East Germany and pretending as though those statements - never codified, never inserted in what became the Final Settlement relating to Germany - were intended to create an agreement, assurance or otherwise on behalf of states that subsequently obtained greater independence.

In the years that followed, declassified documents show the consistency in U.S. policy on this question. Bill Clinton repeatedly refused requests from Yeltsin, and reiterated why the dubious presumption we started this section with is really so dubious ("I can't make commitments on behalf of NATO, and I'm not going to be in the position myself of vetoing NATO expansion with respect to any country, much less letting you or anyone else do so.. NATO works by consensus”).

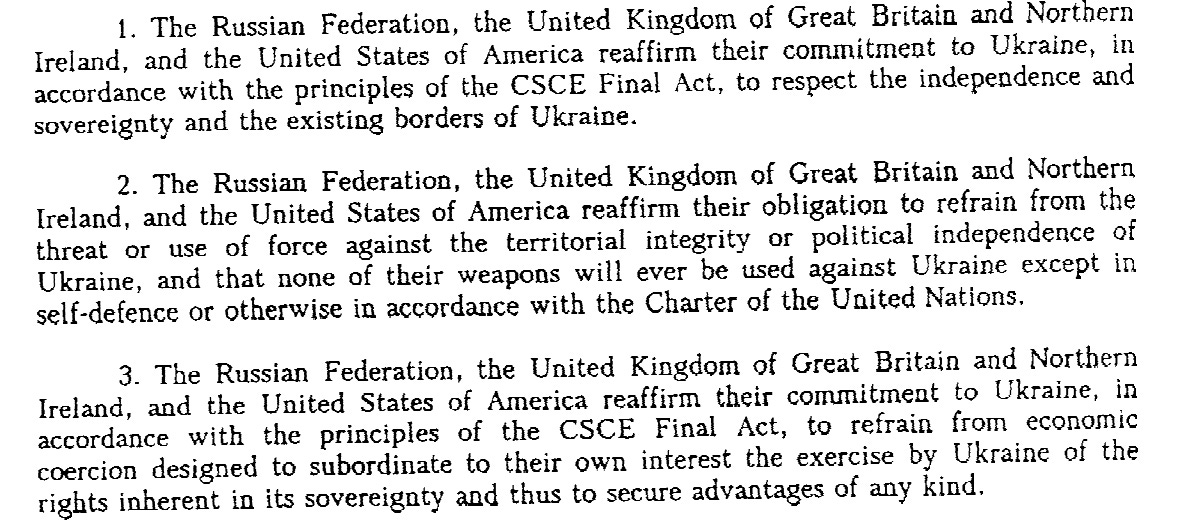

What was in fact endorsed by all parties - in treaties, not vague statements taken out of context - was that there should be “respect for sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of all states and their inherent right to choose the means to ensure their own security”. This was followed by the Budapest Declaration which couldn’t be clearer about Ukraine:

2. Did the expansion of NATO cause Russian aggression?

The short answer is, simply, not in any legitimate way. What follows is an elaborated case for the following:

NATO is a defensive bloc, with a history of acting non-aggressively; Russia is an aggressive actor which has a history of acting aggressively and attempts to argue it requires a Zone of Influence fail on that ground alone though that argument also denies sovereignty to emerging states.

NATO expansionism as an explanation for Russian action fails to acknowledge the role of (i) ideology; (ii) the timing and causes of Russian action; and (iii) the expansionist actions of the Russian state.

NATO expansion has prevented Russian aggression; indeed, it is the failure to expand quickly and uncertainty on membership which has emboldened Russia.

(i) NATO’s reason d’être & overtures and Russia’s aggression

NATO’s cautious and slow expansion

It might seem trite, but its worth stepping back and laying out exactly what the purpose of NATO is, and the behaviour of the Russian state the apologists are seeking to 'explain’.

NATO is fundamentally a defensive bloc, entered into voluntarily by states who wish to be part of the alliance. NATO does not start wars of aggression. With the exception of Kosovo, NATO has never entered a country (i) without the express permission of the country involved or (ii) without an attack on a member state or (iii) specific authorisation by the United Nations. The latter is the most limited of the three, being used in circumstances such as stopping the massacre of innocents during the Bosnian war, and a peacekeeping effort in Kosovo.

NATO has been dragged kicking and screaming into accepting expansion. Poland had its first attempt to join NATO rebuffed. As we discuss below, the attempts by Georgia and Ukraine to join proved fruitless, specifically because of French and German attempts to frustrate membership because of apparent concerns about Russia. But even outside of membership, the cries of Russian humiliation are grossly overstated as Anne Applebaum explains:

When the slow, cautious expansion eventually took place, constant efforts were made to reassure Russia. No NATO bases were placed in the new member states, and until 2013 no exercises were conducted there. A Russia-NATO agreement in 1997 promised no movement of nuclear installations. A NATO-Russia Council was set up in 2002…

Meanwhile, not only was Russia not “humiliated” during this era, it was given de facto “great power” status, along with the Soviet seat on the U.N. Security Council and Soviet embassies. Russia also received Soviet nuclear weapons, some transferred from Ukraine in 1994 in exchange for Russian recognition of Ukraine’s borders. Presidents Clinton and Bush both treated their Russian counterparts as fellow “great power” leaders and invited them to join the Group of Eight — although Russia, neither a large economy nor a democracy, did not qualify.

It was the West who pressured Ukraine into transferring Soviet nuclear weapons from Ukraine to Russia in the 1990s. The U.S withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, intended to neutralise an Iranian threat is an example of Russia’s duplicity in this context. At the time, Putin himself agreed that the move “does not pose a threat to the national security of the Russian Federation.” Lo and behold, 17 years later, he claims it triggered him to increase nuclear weapons stocks. Even in recent history, the U.S. has generally made overtures to Russia, culminating in concrete measures of cooperation. That is true to the extent that there was at the point Mitt Romney called Russia the U.S’s “number one foe”, legitimate grounds for criticising him for doing so.

Russia as the Black Knight

The next point to consider is whether Russia is entitled to a Zone of Influence outside of its borders. This premise is responsible for much of Russia apologia, so its worth answering this question before looking at more specific issues. In my view, no aggressive state is entitled to a zone of influence - and as we go onto explain, it would be worse for global utility if such a privilege was bestowed onto Russia. But even leaving that aside, we come a-cropper on the same dubious assumption we set out above: a zone of influence being insisted upon is a form of neo-imperialism. Sovereign states want to move toward the Western order - an unsurprising trend, given the enviable levels of economic growth and wealth, historic declines in war and violence, cultural enrichment, and liberty - and those states, the people that make them up, are being denied the ability to shape their own paths and destinies.

When Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, the reaction of the world was not to allow Iraq to have a zone of influence, whether or not Kuwait formed part of a coalition with the Saudis or the Iranians. Appeasing this aggression will not prevent further aggression, but encourage it. In other words, as Brian Stewart says:

Russia has historically made claims to the entire South Caucasus, Moldova, Finland, enormous swaths of Central Asia, and chunks of Northeast Asia. A predictable consequence of granting Moscow a “sphere of influence” is that the Kremlin will endeavor to make it as voluminous as possible. By undermining the security of Russia’s neighbors, and driving them to reinforce their own defense, this policy would stimulate the very insecurity that it seeks to stifle.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves: as a preliminary point we need to be clear about what Russian behaviour we are seeking to explain. If the Russia apologists are correct, “NATO expansionism” should be sufficient or necessary to explain the following aggressive actions and measures undertaken by Russia:

The invasion of Georgia, and the acknowledgment of the purported independence of South Ossetia and Abkhazia in 2008

The invasion of Ukraine, and the annexation of Crimea, Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia in 2016-2022

The failed attempt at a coup in Montenegro, which included an attempt to murder the Prime Minister in 2016-17

The intervention to prop up the butchery of President Bashar al-Assad

The funding of the Taliban in Afghanistan against the Afghan National Army and Western forces

The chemical attack in London against Alexander Litveniko

The chemical attack in Salisbury against Sergei and Yulia Skripal, leading to the death of 1 British national

Even ignoring (largely over-hyped) misinformation campaigns, the failed attempt to subvert and influence the U.S. presidential elections in 2016, the Scottish independence referendum, and elections in France and Germany through hacking and other forms of electronic warfare.

Straight off the bat, it doesn’t take much to realise that a lot of the above is not related to NATO expansionism directly or indirectly. The chemical attacks in the UK are intended to target Russian dissidents, and indirectly send a message to his existing officials. Ah, you might say, but all the other things in the list could be indirectly or directly related to NATO expansionism. But are they?

(ii) What, specifically and granularly, explains aktivnye meropriyatiya?

Ideological factors

First, Russia apologia understates the role of ideology - often what are construed as structural questions relating to external circumstance should instead be correctly considered as ideological dogmas. Putin has three pertinent ideological beliefs:

Putin laments the fall of the Soviet Union, calling its collapse a “humanitarian tragedy” which entailed “what had been built up over 1,000 years” being “largely lost”.

Putin has developed an ideological position whereby there are few sovereign states in Eastern Europe. Putin has invariably claimed that “Ukraine is not a state!”, and that “Kiev is the mother of Russian cities. Ancient Rus’ is our common source and we cannot live without each other”). His officials claim that “there is no Ukraine” but only something called ‘Ukrainian-ness” which is “a specific disorder of the mind”.

Putin is disgusted by what he considers the moral depravity of the West, calling it “Satanic” where every child is apparently “offered sex-change operations”. Only Russia and Putin stand in defence of conservative, traditional values against “genderless and fruitless so-called tolerance”, a battle which is akin to “good and evil”.

This isn’t a ‘Great Man of History’ point. It is the second of these that is supported by an ideological superstructure inside Russia; the Kremlin’s reading suggestions for its officials includes Berdyaev, Solovyev, Ilyin - the core message being "Russia’s messianic role in world history, preservation and restoration of Russia’s historical borders and Orthodoxy". This bleeds into fiction, with the ‘Kremlin’s favourite book’ (Mikhail Yuriev’s The Third Empire: Russia as It Ought to Be) being a tale - published in 2006 - in which “Vladimir II the Restorer” annexes eastern sections of Ukraine, followed by a referendum (which, of course, supports 'reunification') before slowly expanding to Belarus, Prednestrovie, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, South Ossetia and Abkhazia.

Was this ideology itself related to NATO expansion? No, as explained by Kimberley Marten (1999):

Scholars disagree about exactly when the shift in Russian domestic thinking about foreign policy became entrenched, whether it was 1992 or 1993. But as Anne L. Clunan notes in her masterful study of Russian identity in the 1990s, by 1992 69 per cent of the Russian public favoured Russia ‘ensur[ing] that she remains a great power, even if this leads to a worsening of her relations with the surrounding world’, and ‘by 1994, the liberal internationalist national self-image had been discredited for ignoring Russia’s past greatness … Most of its proponents had been removed from office and replaced with statists. Russian foreign and domestic policy shifted toward positions more in line with statist and national restorationist self-images.’ This shift away from liberalism and accommodation happened before any consideration of NATO expansion had gone beyond White House walls.

This toxic ideological cocktail must carry great weight in explaining the actions of Putin, rather than an almost two decade old expansion of NATO. Angela Stent in Putin’s World explains the pertinence of this fruit cakery in comparison to NATO expansionism as follows:

NATO enlargement [.. is] only one of the reasons for the deterioration in Russia’s relations with the West. The more important reason is that Russia has not, over the past quarter century, been willing to accept the rules of the international order that the West hoped it would. Those included acknowledging the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the post-Soviet states and supporting a liberal world order that respects the right to self-determination. Russia continues to view the drivers of international politics largely through a nineteenth-century prism. Spheres of influence are more important than the individual rights and sovereignty of smaller countries. It is virtually impossible to reconcile the Western and Russian understanding of sovereignty. For Putin, what counts is power and scale, not rules.

Putin had these views, including specifically about Georgia, long before the NATO expansion in 2004, and long before Georgia’s NATO membership was on the cards. This malign ideology is a necessary condition for Russian aggression. Even if you fallaciously thought that Russia was being “provoked” by NATO’s expansion to fully consenting sovereign states, that conclusion would be rendered meaningless in the context of explaining and justifying this specific Russian action unless you wanted to give succour to this ideology.

In this context, the difference between rationality and paranoia has to be acknowledged. Russia has for the most part avoided direct military conflict with NATO, knowing that an escalation would be catastrophic. But its leadership is myred in paranoia about Western aggression, notwithstanding the steps taken to assuage its concerns. This extends to ridiculously seeing every step taken as somehow being against the Russian state. Trenin explains how it reacted to domestic upheavals in Eastern countries, primarily against corruption, as a Western offensive:

Rather than regarding them as eruptions of popular anger against corrupt and uncaring authorities, and made successful by splits within the ruling elites including the local security services, it saw them as part of a U.S.-conceived and led conspiracy. At minimum, these activities in the Kremlin’s mind aimed at drastically reducing Russia’s influence in its neighborhood, and expanding the United States’. At worst, they constituted a dress rehearsal for exporting a revolution into Russia itself, culminating in installing a pro-U.S. liberal puppet regime in the Kremlin.

A lesson in history: aktivnye meropriyatiya in Georgia

We now come to the more granular explanation for why Russia became aggressive. Putin’s view that only limited sovereignty should exist in Eastern Europe - both because he believes in an expansionist Russia, and because of the rogue view that these states are subservient - leads to wanting to coerce and strong-arm states, whether or not the West is involved. The sovereign states wanting to turn Westwards for legitimate reasons relating to the rule of law, democracy and the economic growth doesn’t work for Russia, and so active measures are taken. Those measures - in themselves - reinforce looking to the West. We can see this plainly through the history of post-Soviet Georgia.

In 1992, following the fall of the Soviet Union and long-before NATO was proposing to expand, there was a long-history of Russia refusing to allow Georgia its newly obtained independence. Tornike Gordadze explains the relationship in the The Guns of August how even in those early days, Russian interference in Georgian affairs was insidious. First, the regime of Gamsakhurdia. Gordadze explains “there are now many indications that Russia backed the coup that ousted Zviad Gamsakhurdia from the presidency in December 1991–January 1992.” Why? “Moscow viewed Gamsakhurdia as a Russophobe and as a danger to Russia’s dominance over the entire Caucasus.”

The replacement regime didn’t fare much better:

…the regime of Eduard Shevardnadze, presumed by many to be loyal to Moscow, turned out to be as attached to the idea of independence and sovereignty as its predecessor, the Gamsakhurdia regime, had been. Russia, in order to impose its hegemony, had somehow to punish this new regime. Yet during this period it became clear that no serious political force in Georgia would ever be so obedient to Moscow as to abandon its sovereign- ty and territorial integrity.

The Russian government at one point backed both sides whilst it considered whether to drop its ambitions for regional hegemony. But that soon changed. The immediate spark for the Abkhazia War 92-93 was a group (associated with Gamsakhurdia supporters) kidnapping the Minister of Interior, leading to Shevardnadze to send troops into Abkhazia. The ultimate result was the re-assertion of Georgian control in Abkhazia, and the secessionist forces moving to Gudauta. That location is important as it housed a Russian military base.

The tide in the war changed but the Gamsakhurida forces were not the only group the Georgian government was fighting. The Russian military provided secessionists in Abkhazia with arms; members of the Russian military were involved in the conflict. The Russians even used their airforce to bomb Shevardnadze’s forces. Thomas Goltz writes in Georgia Diary of a familiar pattern of Russian duplicity:

Even when the Georgians managed to shoot down a MIG-29 and recover the body of the dead Russian pilot with all his papers, the Kremlin refused to admit any in- volvement. Confronted with the evidence, the Russian minister of defense, Pavel Grachev, denied that any Russian aircraft were operating anywhere near the theater—and then charged Georgia with terror-bombing its own citizens. When it was pointed out that the markings on the aircraft were dis- tinctly Russian, Grachev blithely replied that the Georgians had painted his country’s insignia on the plane in order to disguise it.

The forces fighting against Shevardnadze began to make ground, and even though Shevardnadze had previously been a champion of territorial integrity, he was

… obliged to fly to Moscow to beg for Russian military support to fend off a bid by Zviad Gamsakhurdia to rally support among the war-exhausted and shocked population to restore him to power, and Yeltsin (and the top military brass) obligingly did so, thus graphically (if only temporarily) restoring a Russian sphere of influence in a break-away South Caucasus state

Stephen Blank in his chapter in the The Guns of August explains the nuanced position of this support and interference:

Russia’s initial activities in Georgia in 1992–94, where Moscow either ran guns to the Abkhazians or unilaterally imposed its forces as so called “peacekeepers” in the conflicts between Georgia and its rebellious provinces and forced Georgia to accept that verdict, revealed that during this period Russian armed forces were not fully under control…

Every analysis of Russian policy at the time concluded that the main driver was the military, which acted largely on its own. Russian officers were motivated by their hatred for President Eduard Shevardnadze of Georgia (because they attributed to him the breakup, if not handover, of the Soviet empire), a longing to regain their Soviet era vacation homes in Ab- khazia, and a desire to carve out an independent sphere for themselves in the making of Russian defense policy

Why is all of this important? Because it shows the instability and interference of the Russian government in Georgia’s affairs, for reasons entirely unrelated to the West and driven by local factors and expansionist ideology. Indeed, the West pretty much ignored what was going on the region at the time. As is explained by Gordadze in The Guns of August:

…events demonstrate that the West accepted almost everything Russia undertook in the Caucasus in the name of stability. The West strikingly lacked any willingness to get involved in the region. America’s presence was very limited, and the ad- ministration of George H.W. Bush validated and even welcomed the crea- tion of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), which from the very beginning Russia defined as a zone of its own particular interest.

Russia, again, bombed Georgia territory in 2002; long before the Bucharest discussions on Georgian membership of NATO. Amusingly, at the time, Russia denied it was involved in the bombing at all - another claim that is entirely bogus, but its denials in this context are important because an admission would be a clear acceptance that it was the aggressor.

Fast forward to the Rose Revolution and the ousting of the pro-Russian, corrupt leadership rife with electoral fraud, and the role of the Russian government is much the same. Following the arrival of would-be reformist, Mikheil Saakashvili onto the scene, Georgia turned west-wards. In an attempt to undermine Georgia’s territorial integrity, Russian passports were offered to citizens of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Trade embargos, as well as deportations and restrictions in Russia of Gerogian citizens escalated.

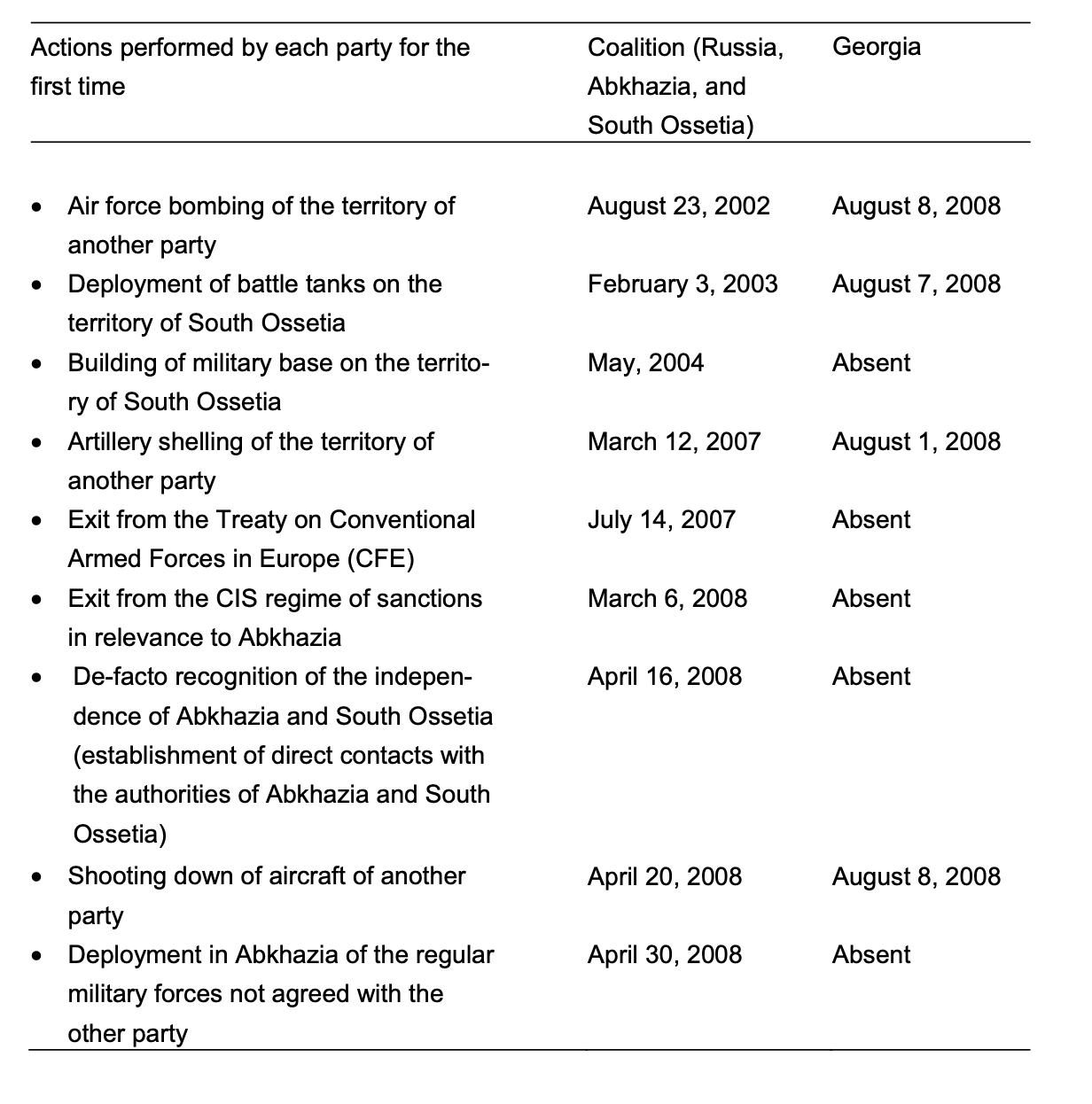

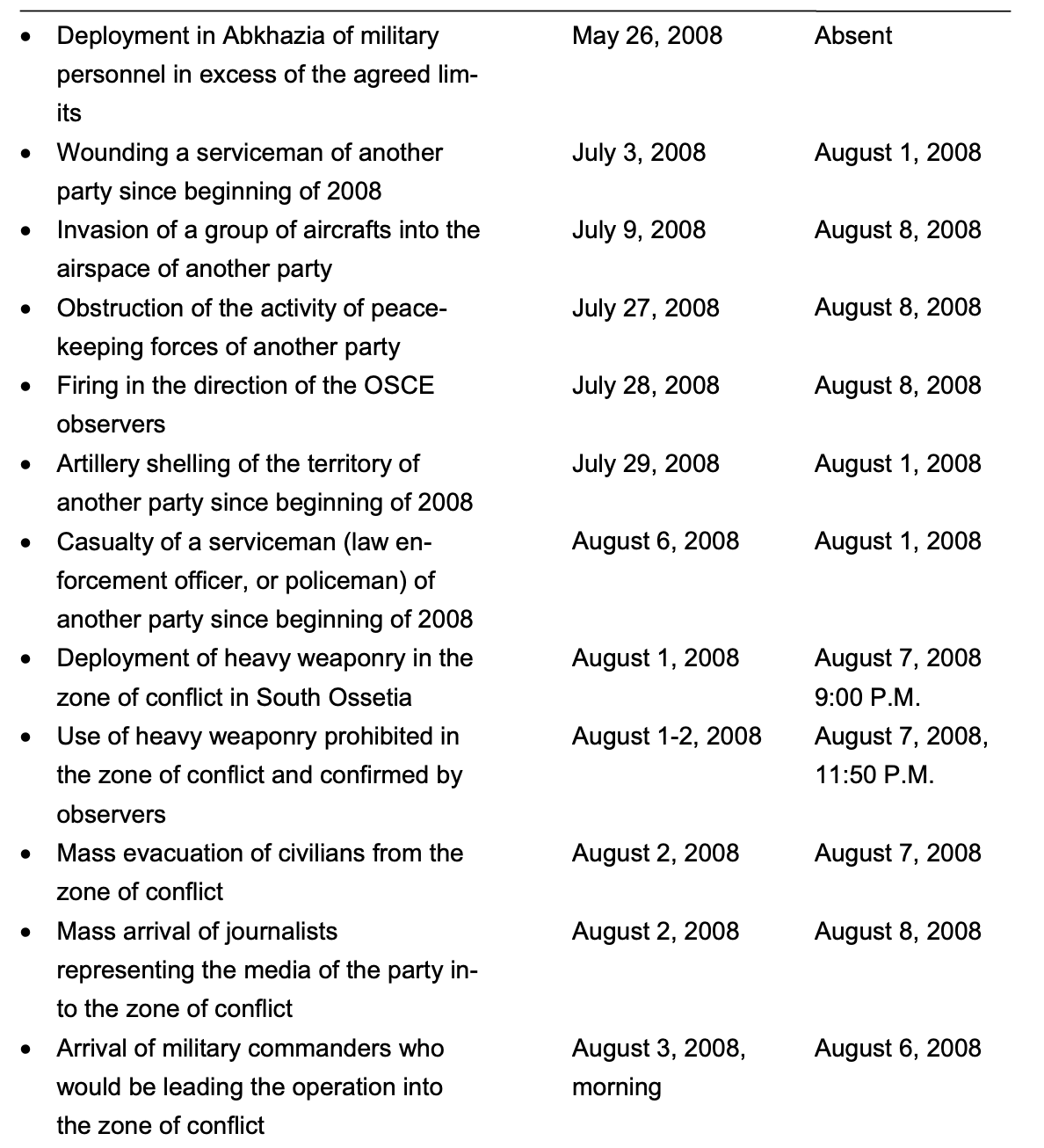

Looking at the history of the build up to the Georgian War, it is clear that every single act of aggression was undertaken by Russia, not Georgia, first:

You could try to argue that the steps after the mid-2000s were related to NATO expansion, but you’d be ignoring a consistent pattern of Russian behaviour inside Georgia’s borders whether or not the West was interested in the region. That behaviour explains why European countries want to join NATO and as we discuss further below, the lack of NATO expansionism probably explains Russian aggression much more. But looking at its actions - even in isolation - ignores that Putin’s ideology simply gives very little weight to territorial integrity of his near neighbours and that a concerned effort Westwards (even where there is no harm to Russia), will be met with aggression.

The story of Ukraine follows the same pattern as Georgia: there is a long line of intervention and interference by the Russians in Ukraine, based on its expansionist ideology. Going back as far as 2004 - again, long before the 2008 membership discussions - Russia interfered in Ukraine’s elections, imposed trade embargos when it got closer to the European Union (leading directly the Maidan protests), attempted to assassinate a prospective leader, long before we get close to its illegal annexation of Crimea.

The most important of those was the desire not to join NATO, but to sign an agreement with the European Union on economic cooperation. As Jeffrey Makoff explains "for all the Kremlin’s angst, Ukrainian membership was never a near-term possibility… it was Yanukovych’s aspiration to sign a trade agreement with the European Union (not NATO) that precipitated the Maidan protest movement and Russia’s first invasion."

What particularly perverse about the NATO expansionism line in relation to Ukraine is that “in reality, the Obama administration made clear it would not promote enlargement further to the East as part of its broader “reset” strategy back in 2009”. It was a pretty open secret, following the clearly fudged statement in 2008 (discussed below) “nobody [in Brussels] expected Ukraine to join the alliance soon, if ever.” People were predicting war between Ukraine and Russia all the way back into the 1990s long before, and unrelated to, NATO expansionism and Ukrainian membership was on the cards.

Ukraine and Georgia are not unique. Moldova has part of its territory occupied by Russian and Russian-backed military forces. In 1999, Russia agreed to evacuate its forces, but “Putin halted the withdrawal in 2003, however, after Moldova’s President Vladimir Voronin refused to sign a peace deal that would have ended the conflict in exchange for accepting Russian military bases and other rights for Moscow”. Those ‘rights’ included a right “keep a Russian military presence and have veto powers on Moldova’s future foreign and security policies”.

In Montenegro, a trial continues into a coup attempt in 2016, unsurprisingly concocted by Russian intelligence. Russia is in the process of destabilising the relationship between Bulgaria and Macedonia in order to prevent European integration. Estonia suffered crippling cyber attacks at the hands of Russia, preventing citizens from banking and government from communicating, caused by the mere movement of the Bronze statue in Tallinn. What inevitably follows is a desire from a sovereign nation to break loose.

3. What would Vlad Do?

Membership of the alliance has successfully avoided a confrontation between NATO members and Russia. It is clear that though Putin is fuelled by a toxic ideology, he remains a rational leader which responds to incentives and a desire to avoid a direct confrontation with the West. Tom Chivers makes the following point about nuclear deterence, but it applies equally well to NATO membership:

This is exactly the logic of nuclear deterrence. Obviously, a nuclear war is completely terrible, and there is no situation in which it is rational – after the fact – to launch nuclear weapons. Even if you’ve just had your capital city turned to glass, it doesn’t help if you then launch a terrible vengeance from your fleet of submarines. It won’t bring anyone back and it just kills a bunch of innocent people. But before the fact, it is important that your opponent believes you will carry out your threat. Otherwise they could blow up all your cities and end the nuclear stand-off without worrying about retaliation.

But the converse is also true: we have very clear examples of how not expanding NATO has led to aggression toward Georgia and Ukraine. As I mentioned above, there was no short or medium term prospect of Ukraine joining. And here lies an area of where Western action may be related to Russian aggression: blurred lines and acting slowly. At the Bucharest Conference in 2008, France and Germany resisted Membership Action Plans for both states, and instead a fudged statement was released stating that they would be members one day. That was Putin’s Green Light: acting in Georgia, knowing that NATO would not act in defence of non-members, followed by Ukraine. Ivo Daalder makes this point in his Economist essay:

The problem is not that NATO enlargement went too far. The problem is that it didn’t go far enough. If Ukraine had been a member of NATO—if American and NATO troops had been deployed to its territory to defend the country—Mr Putin would have thought twice before starting a war with a nuclear-armed alliance militarily superior to his own army. That is the potency of deterrence. With American and NATO troops on the ground, the onus of starting a war with NATO would have been on Russia. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the onus to intervene and go to war is on NATO—not Russia.

Second, we can think more counter-factually about what would have happened without NATO expansion and indeed, other counterfactual situations. Somewhat amusingly, John Mearsheimer (1990) wrote that a scenario in which NATO simply ceased to exist would mean “the prospects for major crises and war in Europe are likely to increase markedly ”. That conclusion is no doubt correct, noting that up until that point relative-peace in Europe depended on a bi-polar-super-power structure, with both the U.S and the Soviet Union armed with nuclear weapons. Mearsheimer explains how the absence of a counter-weight, and new independent states, means that the multi-polar relationships are more likely to arise and then engage in conflict. There is one aspect of his case that is worth underlining, and which supports Section 2 above:

The Soviet Union also might eventually threaten the new status quo. Soviet withdrawal from Eastern Europe does not mean that the Soviets will never feel compelled to return to Eastern Europe. The historical record provides abundant instances of Russian or Soviet involvement in Eastern Europe. Indeed, the Russian presence in Eastern Europe has surged and ebbed repeatedly over the past few centuries. Thus, Soviet withdrawal now hardly guarantees a permanent exit

How right he was! The scenario where NATO doesn’t expand, and exists in name only is somewhat - though only marginally - different from a scenario where NATO doesn’t expand but continues to exist. In that scenario, it is not difficult to see how a nationalist Russia would inevitably lead to central and Eastern European being driven to nuclear weapons, or creating its own collective defence arrangement with little success given the absence of the Western guarantee.

Paul Poast sets out a number of different scenarios in this thread, looking at 8 possible worlds, concluding that NATO expansion is far from a mistake. I’d recommend reading the whole thread, but its worth noting that “Possible Worlds” 3-5 where NATO doesn’t expand: Possible World 3 ends up in a major war in Europe; Possible World 4 leads to Europe being stable, but wide-spread nuclear proliferation (a situation which I'd suggest is not good compared to the status quo); and Possible World 5 requires complete acquiescence of Russia and relies on European and Caucasus countries doing the same.

4. Western peace keeping vs. Russian piece-keeping

I used to spend a lot of time trying to refute claims that Islamist terrorists were attacking innocent people across the world because of Western action. al-Qaeda is clearly a very different beast from Russia (and none of this should be taken as making a claim of comparability). The reason for bringing them up at all is that I am reminded of references invariably being made to extremely vague and broad grievances as explaining and justifying terrorist behaviour.

If you forgive me a brief tangent - consider the broad claim that al-Qaeda was against U.S. “expansion” in the Middle East (and particularly Saudi Arabia). The irrelevance of this broad claim quickly falls away when you consider the group’s first attack. Contrary to popular dramatisations, their first attack was in 1992 in Aden, Yemen targeting U.S soldiers on their way to Somalia. Why were the U.S. soldiers on their way to Somalia? They were part of Operation Restore Hope: an effort to deliver humanitarian aid and food to a humanitarian disaster zone culminating in an estimated 100,000 lives being saved.

The lesson here is that what is argued to be a legitimate grievance evaporates very quickly when you consider the specific attacks in question. In the al-Qaeda case, it evaporates for several reasons: the most obvious being that helping the delivery of humanitarian aid is a good thing, and a threat to carry out terrorism because of it should be squashed, not acquiesced. But there are other reasons the broad grievance falls away as a justification for their actions: the fact that Bin Laden had his goals both before and after the U.S. being in Saudi Arabia; the fact that the victims of his attacks do not have a direct nexus with his aim; the fact that terrorism is not a successful mechanism to reach your goals in any event; and the fact that the regimes they seek to establish are vile and so on.

What has this got to do with Russia and NATO? It is clear from the above, that being members of NATO reduces the amount of Russian dominance, control over a sovereign state, even leaving aside the palpable reduction in threat relating to a direct attack. But the expansion of NATO had led to extremely positive utility gains, and it would take a lot to justify the claim that it is on balance bad (even if you thought NATO expansion was ‘provocative’). In order to join NATO, the membership action plans set out the following requirements:

The first chapter -- political and economic issues -- requires candidates to have stable democratic systems, pursue the peaceful settlement of territorial and ethnic disputes, have good relations with their neighbours, show commitment to the rule of law and human rights, establish democratic and civilian control of their armed forces, and have a market economy

For reasons I’ve explained elsewhere, I’m generally sceptical of external forces leading to being decisive in democrastising countries, but there is some small effect. I wrote a long article on how the idea that the West was “propping up” dictatorships in the Middle East was a pretty bogus idea that overstated the impact of the West, and understated the role of domestic institutional conditions (and oil). I also mentioned that there were Black Knights in international relations; the West would, within those domestic constraints, push toward liberal/democratic norms and systems and Black Knights would do the opposite. That post explicitly highlighted Russia as an example of a Black Knight.

In that vein, in line with that expectation, there are specific reasons to be sceptical that NATO is solely responsible for increasing democratisation in the Bloodlands and the Baltic. The fact that many candidate states also wish to join the European Union introduces a further confounding factor. That said, there is some White Knight behaviour here. Rachel Epstein (2004/5) notes, NATO effectively shamed Poland into ensuring civilian control of the military, and then goes onto explain how other countries were and could be subject to that influence. Civilian control of the military has dozens of positive effects, but one wry benefit to note in particular is astutely noted by Edward P. Joseph:

More than anything, NATO and EU accession required aspirant countries to incorporate liberal, western values like pluralism, civilian control of the military, rule of law and respect for human rights. In Crimea and Eastern Ukraine, Russia today asserts the need to protect the security of the ethnic Russian minority as justifying intervention. With more than a million ethnic Russians and Russian citizens living as minorities in the three Baltic states, there are rising concerns that Moscow might create a pretext to intervene in one or more of these states despite the fact that each is a NATO member. It may matter little to the Kremlin, but the fact is that the rights of ethnic Russians are better protected and more strongly regulated by virtue of the Baltics having acceded to both NATO and the EU. Contentious issues like citizenship have been addressed in a largely transparent manner. In sharp contrast with Crimea and Eastern Ukraine these days, international human rights actors like the OSCE’s High Commissioner for National Minorities have unchallenged access to Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania in order to examine and report on the situation of the Russian minorities there.

There is wider evidence of this as well. Gibler and Sewell (2006) support the idea that the resistance to Russian threats provided by NATO led to stronger, and more stable, democracies. In particular, “states that quickly adopted democracy while also moving away from Russian influence tended to retain stronger democratic regimes, with greater stability, than states remaining within Russian influence”. They conclude that “expansion of NATO eastward therefore aided the creation of a peaceful environment for democracy to survive”. Gheciu (2005) finds another avenue in which NATO has contributed to liberal democratic norms through socialisation.

The wider point in my Black Knights post was that Western engagement was beneficial, even if only pushed countries in the right direction. Levitsky and Way’s book on the subject is largely persuasive. Since I wrote my post, my conviction in that view has strengthened. There are specific studies showing how NATO and other encourage democratic contagion.

I also don’t think the problematic issue of determining the respective contribution of the EU vs. NATO matters in this particular context: Russia objects to both. Here the evidence is much stronger. Poast and Chinchilla (2020) show that being an EU applicant, as well being both an EU and NATO applicant, have substantial and statistically significant effects on democratisation. These are all tangible benefits such that even if you thought NATO expansion was ‘provocative’, it would still be worth it.

We have spent quite a while talking about NATO expansionism, but we should also note the following:

In 1992, there was an ethnic cleansing campaign in Bosnia; the West created a no-fly zone over Bosnia to protect the civilian population, enforcing the terms of UNSC Resolutions to disrupt Serbian-Yugoslavian attempts to target the Croat and Muslim population.

In 1995, Mladic captured a “safe area” of Srebrenica, killing about 8,000 Muslim. NATO intervened, carrying out air strikes in Sarajevo.

In 1999, an attempt to genocide the ethnic Albanian population by Yugoslav forces. NATO intervened.

In 2008, Kosovo declared independence, and the West rightfully recognised it is a separate and sovereign state.

It is beyond the scope of this post to go through the detail of these interventions, but it is important to note that each of these is, cumulatively, as much of a ‘provocation’ to Russia as NATO expansionism. Kosovo, alone, pales in comparison to the expansions in 1999 and 2004. In the case of the earlier NATO interventions, these occurred long before NATO expansion, or were completely unrelated to expansion. As Kimberley Marden notes:

In the end, there may simply have been too many conflicts of interest between NATO (and the US in particular) and the Russian military organisation to make PFP [Partnership for Peace] truly work... Even without NATO’s geographic expansion, PFP could not have overcome the sense that NATO’s role in global security affairs was growing at the expense of Russia’s statist and nationalist definition of its own security interests.

That underlines the point that NATO expansionism does not explain Russian behaviour, but also that if we went along with the Russia apologia, we would not have saved tens of thousands of lives and prevented conflicts on Europe’s doorstep for the last 3 decades - something which must surely lead us to conclude that NATO’s expansionism and interventions are to be lauded, not criticised.