“The BBC Is the U.K.'s Biggest Soft-Power Weapon” - so said a Bloomberg opinion column earlier this year. This is often the context in which ‘soft power’ is discussed in the UK.

It reminds me of the anecdote from Peter Bergen’s The Longest War: The Enduring Conflict between America and Al-Qaeda: Bin Laden, prior to the 9/11 attacks, instructed his men to ensure they had reception so they could watch the attacks unfold on TV. As it happened, they couldn’t get the antenna to work so they ended up listening to the reports for each of the three attacks on the BBC World Service (after each attack, Bin Laden would raise his hand to silence his cheering followers, telling them more would follow).

I don’t mean to suggest that the BBC is bad because Bin Laden used it on 9/11; the truth is I don’t know whether its a good, effective form of soft power. It does make me think though: what does effective, evidence-based soft power look like? Here are three ideas.

1. Free education (for plutocrats)

We know that education matters: Stuart Ritchie et al (2018) look at 42 data sets, covering over 600,000 participants, and find that an additional year of education improves IQ by 1 to 5 points. We also know that education matters for political outcomes: Tim Besley and his colleagues (2011) wrote a seminal paper entitled “Do educated leaders matter?” in which, as you’d expect, he explores whether having more educated leaders affects the rate of economic growth. The paper is vast, and looks at over 1,600 leaders in 197 countries, covering the period between 1870s and the 2000s. They find that the departure of an educated leader leads to a 0.7pp drop in the growth rate per annum but for an uneducated leader the drop is only 0.05pp. A transition from a leader with a post-graduate education to one without yields an average reduction in growth of around 2.1pp over 5 years.

Does this have any relevance in the world of foreign policy? Maybe. What if being educated in the West made authoritarian countries less authoritarian because of the absorption of Western norms? What if it helped with state capacity by directly providing leaders with skills, or indirectly by establishing a network of their (elite) countrymen which could form a technocratic cabinet? What if it allowed them to build relationships with political elites in the West? Consider the following:

President Teng-hui of Taiwan (Cornell) took over from Kai-shek, introducing a flawed, but significant, series of liberalising reforms; he subsequently wrote that his time at Cornell was when he “first recognized that full democracy could engender ultimately peaceful change, and that lack of democracy must be confronted with democratic methods, and lack of freedom must be confronted by the idea of freedom before it would be possible to hasten the day of genuine democracy and freedom”.

President Mikheil Saakashvili of Georgia (Columbia Law) filled his government with technocrats (also educated in the West). He used his contacts in the West to obtain funds and other assistance in reforming and investing in Georgia.

President Óscar Arias of Costa Rica (London School of Economics, University of Essex) was involved in the Esquipulas Peace Agreement, and was awarded the Albert Schweitzer Prize for Humanitarianism.

President Alassane Ouattara of Cote d’Ivore (University of Pensilvania) was able to ‘‘draw on friends in high places made in western capitals during the 1980s and late 1990s’’ to invest in his homeland (Wallis 2011).

If these are not just fun little gobbits and anecdotes, it might be a good idea to spend sums of money - it doesn’t have to be the size of the BBC’s budget! - educating elites from across the developing world, particularly those who are likely to be close to power. Is it the case?

We need to be careful because there is inherently some degree of openness baked into a future foreign leader who wants to attend a university in the West. We also need to be careful because the record isn’t as clear cut as the above suggests (e.g. Abdullah Gul, former Prime Minister of Turkey who pushed his country in an Islamist direction, attended the University of Exeter; the Butcher of the 2010s, Bashar al-Assad, studied at the Western Eye Hospital in Marylebone, Théoneste Bagosora, a main character in the Rwanda genocide, was educated in Paris). In some cases, presence in the West is a facilitating or seemingly radicalising factor (e.g. Pol Pot joining the communist party in Paris or the infamous screeds of Syedd Qutb berating the behaviour the purported degeneracy of Americans during his time in the U.S, including a short spell at Stanford).

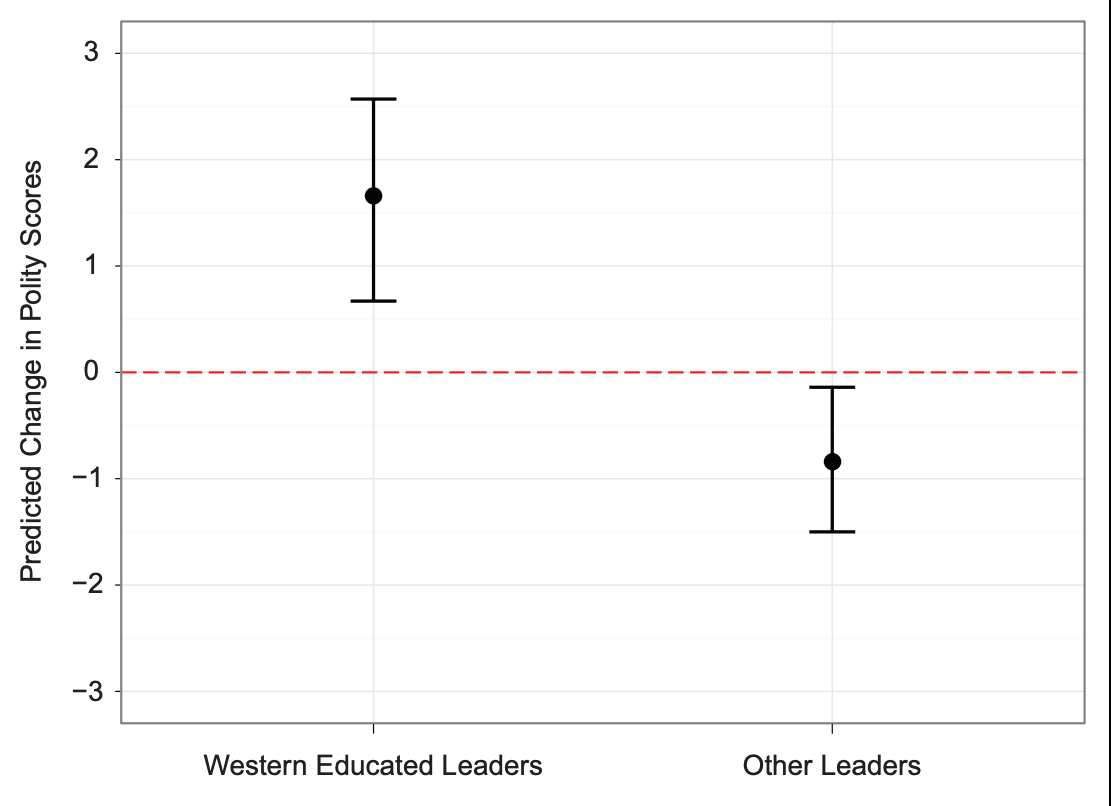

We have a few relevant studies in this context: Thomas Gift and Daniel Krcmaric (2015) look at foreign leaders educated in the West in the context of democratisation. They find that a democratic transition is almost four times more likely with a Western-educated leader compared with an uneducated, or non-Western educated leader (30% vs. 8%).

Gift and Krcmaric aren’t persuaded by one of the endogeneity concerns here (i.e., those who school in the West may are those who are likely to be open to democraticisation or Western norms): they note that some of the most stridently authoritarian leaders like Zimbabwe’s Mugabe or Equatorial Guinea’s Obiang send their children to the West not out of any love for Western notions of polity, but to acquire skills. To that end, they cite various surveys affirming that the aim is to acquire skills, not politics.

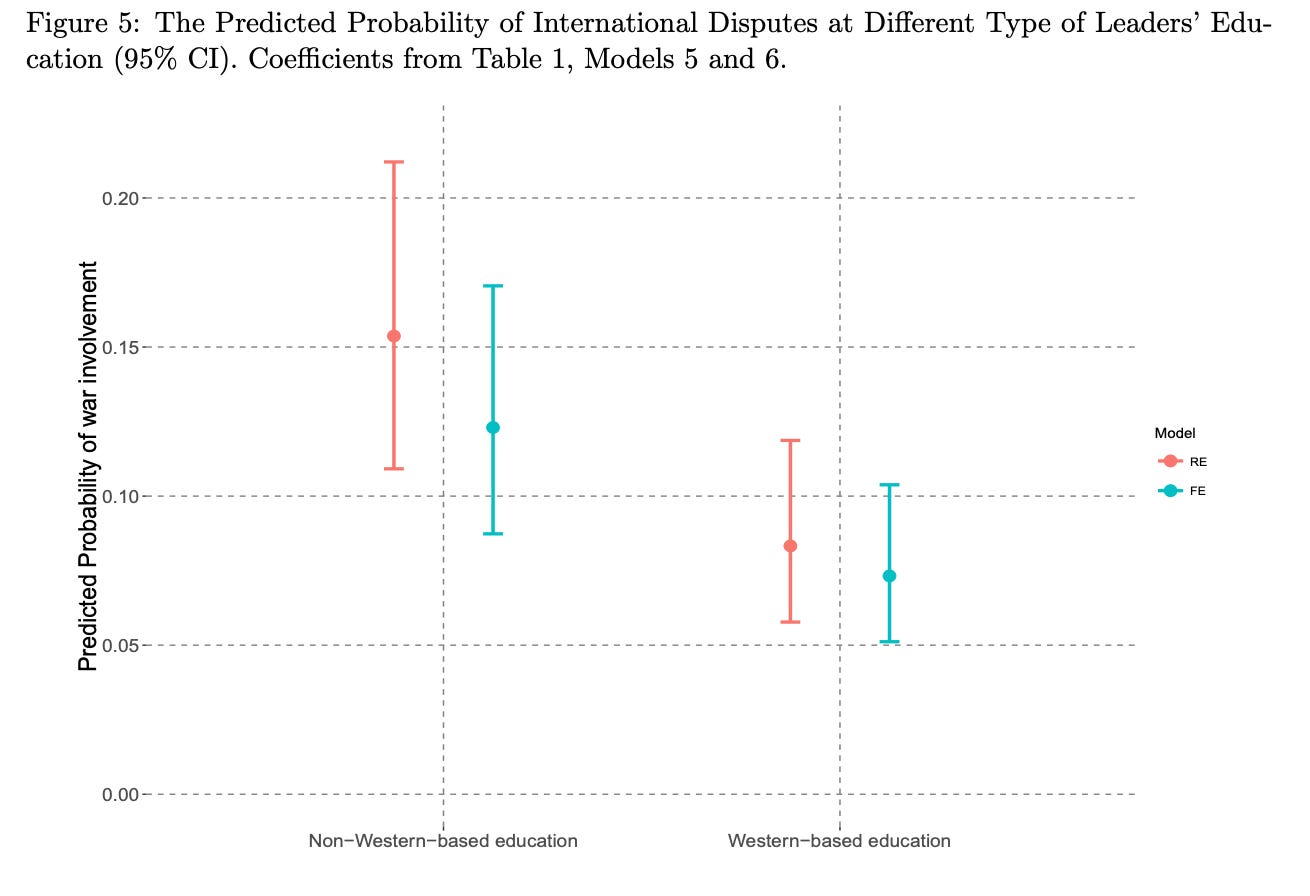

The second study to note is Barcello (2020) who looks at more than 900 leaders from 147 non-Western countries between 1947 and 2001. He finds that even when accounting for leader selection, time-variant country and leader-level controls, Western-educated leaders are less likely to be involved in inter-state military disputes (see Figure 5 below).

This effect need not be confined to leaders either: Carol Atkinson (2010) finds that where states sent their military officers to the U.S., there is an association with improved human rights. Atkinson’s earlier 2006 paper supports the democratiscation finding, showing that across a number of liberalising measures, engagement and exchange with the U.S. was associated with positive outcomes. More generally, Antonio Spilimbergo (2009) finds that having a greater number of students educated in democratic countries is correlated with subsequent democratisations. What is common in these papers is the reference to socialisation and absorption of norms being the key mechanism by which these effects arise.

2. Linkage

I’ve previously written at length about how we should approach international relationships, but here is a summary. In short, building bilateral and multi-lateral relationships opens up the ability to shape, and sometimes force, positive changes.

Levitsky and Way in their book Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War look at 35 countries which became, what they call, ‘competitive authoritarian’ states in the early 1990s. These regimes are not fully authoritarian but take the form of a state like Russia where there is a guide of democratic behaviour. These regimes typically have clear political inequality and mass human rights violations.

Levitsky and Way’s independent variable is Western linkage and leverage. Western leverage is high where a state “lacks bargaining power and are heavily affected by Western punitive action” (p.41). Western linkage is defined as economic (trade or credit), intergovernmental (bilateral economic and military ties), technocratic (country’s elite being educated in the West), social (flow of people between borders), information (flows of Western ideas) and civil society linkage (Western NGOs) (p.43-4).

Linkage works via three mechanisms:

it [i.e., linkage] heightened the international reverberation caused by autocratic abuse [because linkage] increases the probability that... Western governments will take action in response to reported abuse;

it created domestic constituencies for democratic norm-abiding behaviour [in the form of personal, financial and professional ties to the West and] international isolation triggered by flawed elections, human rights abuses [etc.] would put these ties and consequently, valued markets, investment flows, grants, jobs prospects and reputations – at risk; and

it reshaped the domestic distribution of power and resource strengthening democratic and opposition forces and weakening and isolating autocrats [because] ties to Westerns governments... may provide critical resources to opposition and prodemocracy movements helping to level the playing field against autocratic governments (p.44-48, 70).

For countries where linkage and leverage is high, their model predict “external democratising pressure is consistent and intense” and “autocracies are less likely to survive” (p.53). When looking at the studies 35 states, they find their model fits for 28 of them.

Similarly, Daniel Ritter (2015) in his book The Iron Cage of Liberalism provides evidence for the first Levitsky and Way limb described above. Ritter’s argument is that “friendly international relations between the authoritarian regimes in Iran, Tunisia, and Egypt and their Western patrons’ leads to a insincere use of liberal ideals which then ‘constrains authoritarian regimes and their Western allies by holding them accountable to liberal expectations” (p.18-19).

This, in turn, means that non-violent revolutions work because the regimes cannot suppress the people. The idea is that there is an ‘iterative, relation process’ by which (1) the authoritarian regimes, (2) the West and (3) the opposition forces in a society coalesce to create an ‘iron cage of liberalism.’ The West pressures its allies to reform any authoritarian bents that the regime has. The authoritarian regimes respond by espousing democratic ideals without making substantive changes. Ritter refers to this as a ‘façade democracy’ which is a weak attempt to accept liberal, democratic norms.

Opposition forces are strengthened directly by the West funding civil society programmes and the regimes allowing for modicums of reform which allow the emergence of a civil society. By espousing such ideas, citizens also judged their rulers by standards which they obviously fell short of and then accordingly had to offer more. It is these reinforcing mechanisms that lead to the iron cage, and therefore successful non-violent revolutions:

As a result of their close ties to the West, the shah, Ben Ali, and Mubarak eventually found themselves trapped by the liberal discourse they had adopted precisely in order to promulgate their relationships with the democratic world. When large crowds of nonviolent protesters materialized [the regimes were] unable to resort to violence [and] they were swept away by the empty hands of unarmed revolutionaries (p.214).

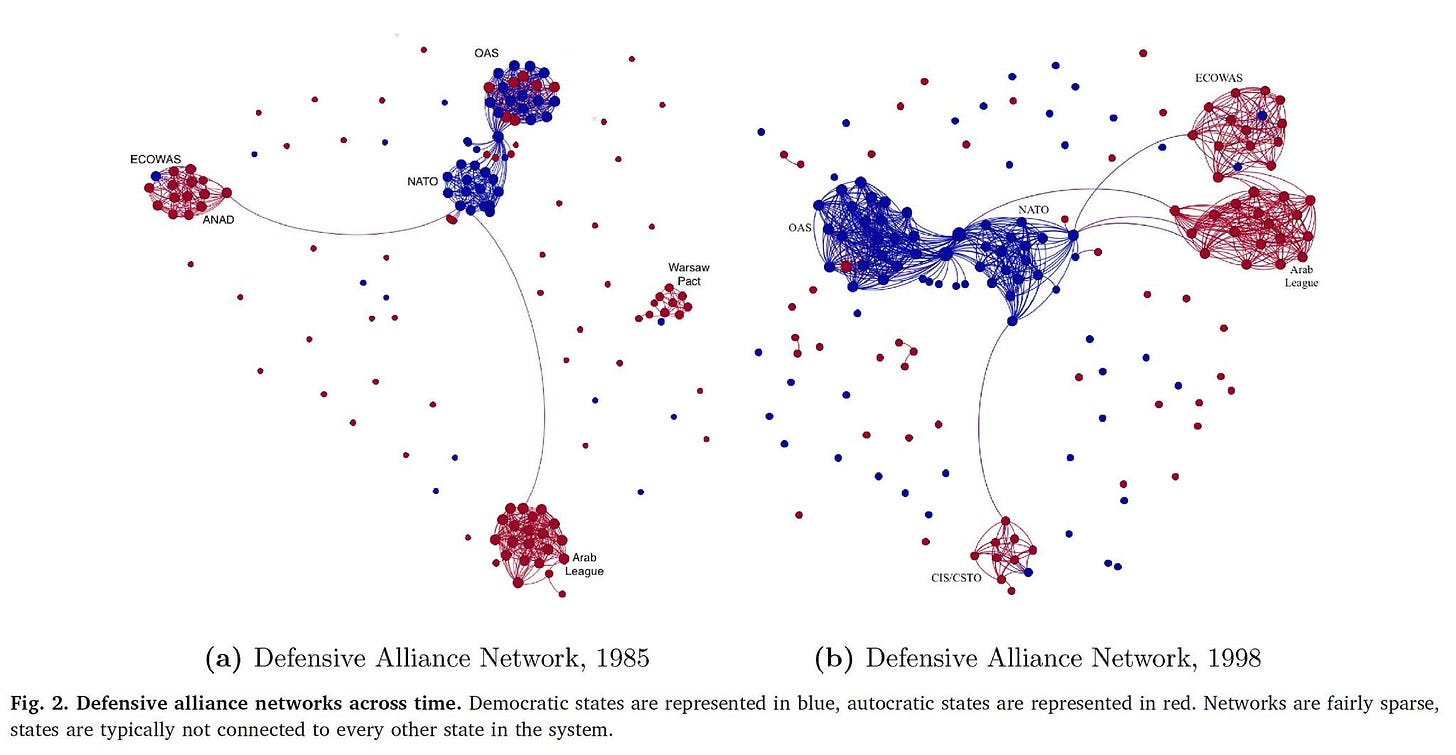

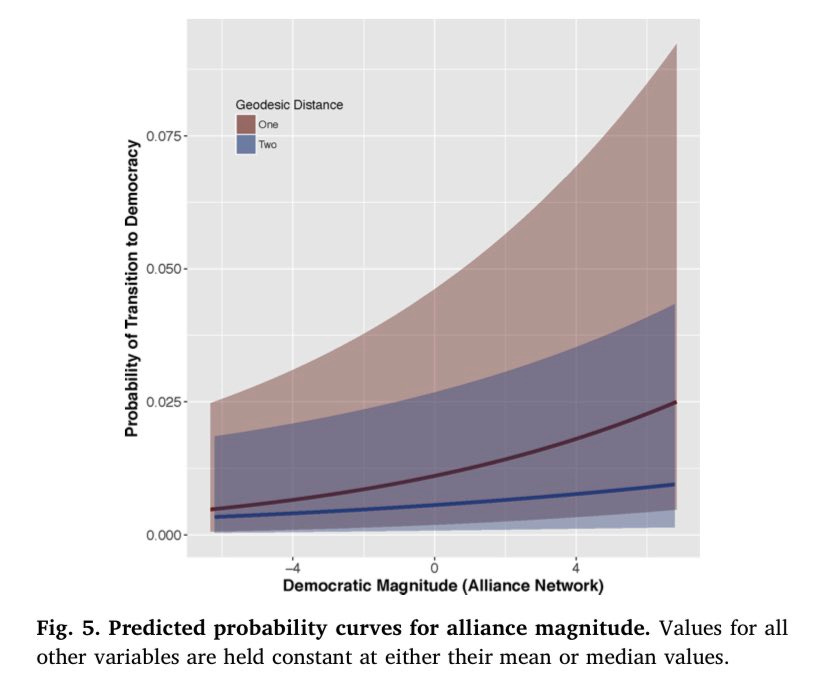

These are not findings confined to 35 post-Cold War states, and North Africa. Skyler Cranmer et al (2020) look at network effects, using “alliance networks” like NATO, ECOWAS, as well as other international organisations, to look at the how participation in them can affect the political economy of authoritarian states.

They find there is a form of “democratic contagion” effect (see Figure 4 below). The mechanisms they discuss in the paper are, unsurprisingly, socialisation and proliferation of Western norms.

Interestingly, they note that military alliances in particular are likely to be “strong incubators for socialisation”. Which brings us to Swed and Weinrib (2015). In a nod to the papers from Carol Atkinson discussed above, they look at 2,523 cases of political unrest between 1996 and 2005. They find “the number of deaths that result from government-initiated response to political unrest is significantly lower where the military is westernized. These differences are particularly notable in poorer settings, and were particularly strong in the pre-GWOT (1996–2000) era.”

Indeed, they find that “among poor countries whose main combat aircraft, tanks and APCs in the pre-1991 era did not come from western countries, we see e1.85 (6.4) more deaths than in wealthier countries. But among poor countries whose main weapon systems in the pre-1991 era did come from western countries, we see e-3.03 (3.7%) the number of deaths.” What is common in all of these is, again, socialisation but the creation of linkages and relationships.

3. Be excellent to each other

The rise of President Trump reignited the debate about whether being a “Mad Man” was conducive to international peace and security. It’s made a resurgence again following the barbaric war of aggression launched by President Putin. The argument goes “if only Putin had to consider an erratic President in the White House, he might have questioned whether to invade Ukraine”. This argument is bogus narrowly because Putin was acting aggressively - to the U.S, the West and in Eastern Europe - throughout 2004 to 2022 but it’s also just not true more generally.

Roseanne McManus (2019) looks at whether being a ‘Mad Man’ helps with general deterrence, and also whether it means that they are able to extract more concessions during a crisis. She look at news articles, coding for when a leader was attributed with some kind of ‘mad tendency’ and then gives them an ‘average madness score’. Saddam is a the the top of the charts with a madness score of 0.516 (for comparison, Tony Blair has a madness score of 0.077). In the period between 1986 and 2010, McManus finds there were 742 militarised inter-state disputes which she analyses using her nifty madness scores. She finds:

The positive and significant coefficient for Leader B in Model 1 indicates that a stronger madness reputation of Leader B makes State B more likely to be targeted in a MID. Similarly, the positive and significant coefficient for Leader A in Model 3 indicates that a stronger madness reputation of Leader A raises the probability that a MID initiated by Leader A will be reciprocated. Thus, contrary to the Madman Theory, these results suggest that perceived madness is detrimental to both general deterrence and crisis bargaining.

The astute advice from Bill and Ted to be excellent to each other is also true in the context of how countries should generally engage with one another. One specific context is meeting the defence spending commitments which all NATO states should do. President Trump apparently once handed Angela Merkel a bill for $300bn for money owed to NATO. Does this kind of shaming work? We have an answer from Becker et al (2019):

Our analysis suggests that allies do not respond to such rhetoric by increasing defense spending, and may even decrease defense spending as a result. In particular, we find that the more negatively US presidents speak about transatlantic burden-sharing, the less allies spend on defense. This result is robust to the use of overall military expenditures as a share of GDP, as well as to the use of the share of equipment and operating and maintenance expenditures (areas both NATO and the EU have emphasized) in GDP. It is also robust to controls drawn from the traditional public choice literature, and to multiple model specifications, including country fixed effects.

As corporatist and cringe as it sounds, soft power should be about building relationships, encouraging the fluid exchange of peoples, establishing robust military networks to allow to the absorption and permeation of norms, and creating the conditions where leverage can effectively be used. It should not be about celebrating instability nor admonishing allies.