This post isn’t designed to convince those who think the Iraq War was Bad, that it was Actually Good. It is a sincere attempt to imagine a world where Saddam Hussein was still in power. I acknowledge that the counterfactuals laid out below were used in the framing in the lead up to the war - but, in any event, any justification found below for the Second Gulf War says nothing about the execution of the war, or US/UK policy in Iraq following the fall of Saddam’s regime.

What would he have done?

As I’ve explained at length elsewhere, those who decry that it perfectly knowable that Saddam didn’t have a sizeable stock of WMDs ignore that Saddam’s policy was explicitly to have strategic ambiguity about WMDs. Saddam’s rationale for this has now long been known: he was more threatened by Tehran and Tel Aviv, than he was Washington or London:

Saddam was asked about the weapons during a meeting with members of the Revolutionary Command Council. He replied that Iraq did not have WMD but flatly rejected a suggestion that the regime remove all doubts to the contrary, going on to explain that such a declaration might encourage the Israelis to attack (Explaining the Iraq War, Harvey (2011), p.251)

Saddam had always had suspicion of Iranians (incidentally, his uncle published “Three Whom God Should Not Have Created: Persians, Jews and Flies”). He explained just as much after he was captured:

Piro: Why would you say something that suggests Iraq has WMD stocks when, as you say, you had been trying to convince the UN Security Council that Iraq had complied?

Hussein: Mister George. You in America do not see the world that confronts Iraq. I must defend the Arab nation against the Persians and Israelis. The Persians have attacked regularly. They send missiles and infiltrations against us. If they believe we are weak, they will attack. And it is well known that both the Israelis and Persians have nuclear bombs and chemical bombs and the biological weapons

This fear, and hostility, to Iran and Israel also has to be seen in the context of the containment regime failing. The sanctions regime the international community had in place was falling apart as the Iraq Survey Group sets out:

The introduction of the Oil-For-Food program (OFF) in late 1996 was a key turning point for the Regime. OFF rescued Baghdad’s economy from a terminal decline created by sanctions. The Regime quickly came to see that OFF could be corrupted to acquire foreign exchange both to further undermine sanctions and to provide the means to enhance dual-use infrastructure and potential WMD-related development.

Containment was waining fast: dozens of countries began to fly flights into Iraq; smuggling was rife and China even had a contract for the delivery of a fibre optic communications network. Benon Sevan, director of the OFF, wrote that he had raised with the compliance group on “at least 70 occasions of contracts reflecting suspicious pricing (and hence possible kickbacks), yet the committee declined in every instance to act.” That containment was failing is entirely encapsulated by the fact that it took 100,000 British and American military personnel arriving on Saddam’s doorstep prior to the Second Gulf War for Saddam to agree to further weapons inspections.

The rationale for this strategic ambiguity, and the failure of containment, provides a good starting point for what Saddam would have done if the world was not looking. But we don’t just need conjecture here: the Iraq Survey Group, having carried out a thorough investigation, and dozens of interviews with regime officials and Saddam himself concluded:

Saddam wanted to recreate Iraq’s WMD capability—which was essentially destroyed in 1991—after sanctions were removed and Iraq’s economy stabilized, but probably with a different mix of capabilities to that which previously existed. Saddam aspired to develop a nuclear capability—in an incremental fashion, irrespective of international pressure and the resulting economic risks—but he intended to focus on ballistic missile and tactical chemical warfare (CW) capabilities.

His desire to regain WMDs wasn’t just a mere inchoate aspiration, the regime took steps to ensure it could revitalise the nuclear programme when the sanctions ended - again, from the Iraq Survey Group:

The Regime prevented scientists from the former nuclear weapons program from leaving either their jobs or Iraq. Moreover, in the late 1990s, personnel from both MIC and the IAEC received significant pay raises in a bid to retain them, and the Regime undertook new investments in university research in a bid to ensure that Iraq retained technical knowledge.

Since the Iraq Survey Group’s findings, Mahdi Obeidi, the Director General of Iraq's Ministry of Military Industrialization under Saddam’s rule, and the man charged with enriching uranium published The Bomb in My Garden in which he explains that following the end of the nuclear programme in the early 1990s, he buried a copy of centrifuge designs and four components just by a lotus tree in his back garden. (Note, Saddam paid North Korea $10m for more conventional intercontinental missiles - which he was also banned from obtaining - in the final months of his regime; a deal that North Korea didn’t satisfy because things were “too hot”).

This isn’t some crackpot theory of neocons - indeed, the UK’s Butler Report concluded much the same:

…we have reached the conclusion that prior to the war the Iraqi regime had the strategic intention of resuming the pursuit of prohibited weapons programmes, including if possible its nuclear weapons programme, when United Nations inspection regimes were relaxed and sanctions were eroded or lifted.

So what?

There are three key implications of Saddam’s regime continuing, and that regime having weapons of mass destruction, and specifically nuclear weapons:

Regional instability, with a knock on impact on international security

A dangerous nexus between WMD and terrorism.

Ongoing and intensified violence against his own people

Regional instability

So far we have focussed on the Iranian threat that Saddam perceived, but its worth dwelling on his plans for Israel if he obtained WMD. The most succinct summary of his views on this is contained in Brands and Palkki (2011):

… Saddam repeatedly returned to the subject of how an Iraqi nuclear capability could be used against Israel. This was a critical strategic and identity issue for Saddam. Although Saddam styled himself as the transcendent leader who would unite the Arabs and defeat the “Zionist entity,” in private he concluded that Israel’s nuclear monopoly in the Middle East made taking major military action to accomplish this goal an unacceptably risky proposition. In the face of an Iraqi or Arab attack, Saddam believed, Israel could simply threaten to use nuclear weapons against its enemies, thereby forcing them to halt their advance.…

Saddam’s aim was not to launch a surprise first strike against Israel; rather, he believed that an Iraqi bomb would neutralize Israeli nuclear threats, force the Jewish state to fight at the conventional level, and thereby allow Iraq and its Arab allies to prosecute a prolonged war that would displace Israel from the territories occupied in 1967. In short, Saddam expected that an unconventional arsenal would permit Iraq to achieve a conventional victory, thereby weakening Israel geopolitically and making him a hero to the Arab world.

Incidentally, there is a common view that nuclear weapons help stabilise international affairs by counterbalancing world powers, and deterring further conflict - a theory that has force for superpowers, but which is lacking for regionally aggressive actors like Saddam. Indeed, as Brands and Palkki confirm, Saddam’s belief was that his chemical weapons meant he could act with impunity during his aggressive takeover of Kuwait in 1991.

Kenneth Pollack’s The Threatening Storm alludes to the fact that much of international affairs literature is obsessed about whether particular regimes are “rational” or not. The point about Saddam is that is his objectives are anathema to peace in the region even where “rational”:

… Saddam has a number of pathologies that make deterring him unusually difficult. He is an inveterate gambler and risk-taker who regularly twists his calculation of the odds to suit his preferred course of action. He bases his calculations on assumptions that outsiders often find bizarre and has little understanding of the larger world. He is a solitary decision-maker who relies little on advice from others. And he has poor sources of information about matters outside Iraq, along with intelligence services that generally tell him what they believe he wants to hear. These pathologies lie behind the many terrible mis calculations Saddam has made over the years that flew in the face of deterrence-including the invasion of Iran in 1980, the invasion of Kuwait in 1990, the decision to fight for Kuwait in 1991, and the decision to threaten Kuwait again in 1994.

It is thus impossible to predict the kind of calculations he would make about the willingness of the United States to challenge him once he had the ability to incinerate Riyadh, Tel Aviv, or the Saudi oil fields. He might well make another grab for Kuwait, for example, and once in possession dare the United States to evict him and risk a nuclear exchange. During the Cold War, U.S. strategists used to fret that once the Soviet Union reached strategic parity, Moscow would feel free to employ its conventional forces as it saw fit because the United States would be too scared of escalation to respond. Such fears were plausible in the abstract but seem to have been groundless because Soviet leaders were fundamentally conservative decision-makers. Saddam, in contrast, is fundamentally aggressive and risk-acceptant. Leaving him free to acquire nuclear weapons and then hoping that in spite of his track record he can be deterred this time around is not the kind of social science experiment the United States government should be willing to run (Pollack, (2002)).

Allowing a regime to obtain nuclear weapons would increase the risk of regional instability, with an inevitable knock on impact on international security. This isn’t just conjecture, it has to be seen in the context of Saddam’s historic and repeated aggression (the Iran-Iraq War, the Anfal Campaign, the (short lived) extinguishment and annexation of Kuwait, the firing of scud missiles at Israel, coupled with a long history of supporting terrorism across the region). No doubt this requires some judgement, but at the very least the view that leaving Saddam in place would lead to regional instability is not unreasonable.

WMD-terrorism nexus

The UK government was extremely careful in not suggesting there was an operational connection between Saddam Hussein and Al Qaeda. Indeed, British intelligence agencies were fairly open about this even at the time. Tony Blair’s case for war was never based on there being such a link either, as he explains in his autobiography:

But for September 11, Iraq would not have happened. People sometimes take that as meaning I'm saying Iraq posed the same threat as Afghanistan, i.e. there was a link to al-Qaeda. I'm not.

So what, then, is the connection between terrorism, WMD and Saddam? Philip Bobbit explains in Terror and Consent that modern terrorism (“market state terrorism”) is fundamentally different from its predecessor (“nation state terrorism”) - the former wants to cause greater civilian casualties and more theatrical destruction:

The conventional wisdom from the 1970s onward was that terrorist groups would not seek WMD for the same reasons that led them to moderate the lethality of their conventional attacks. Fearing popular revulsion, international disapproval, local repression, and threats to their own cohesion, and facing active dissuasion by those states that monopolized WMD even when they were willing to arm terrorists with other weapons, these groups turned away from such acquisitions. If someone had said to either Gerry Adams or Yasir Arafat, “I can get you a ten-kiloton nuclear weapon,” one can imagine the reaction. A cautious gasp, a quick turning away—reflecting the apprehension that one has met an agent provocateur. But suppose such an offer were made to bin Laden? He would say, “What will it cost?”

Indeed, we know that this is what Bin Laden thought via an interview with Time magazine in 1999:

TIME: The U.S. says you are trying to acquire chemical and nuclear weapons.

BIN LADEN: Acquiring weapons for the defense of Muslims is a religious duty. If I have indeed acquired these weapons, then I thank God for enabling me to do so. And if I seek to acquire these weapons, I am carrying out a duty.

Of course, Bin Laden is dead and the mere aspiration, in isolation, of various terrorist groups around the world should not cause us alarm. However, as Bobbit notes “advances in technology are rapidly lowering the thresholds for the development, deployment and deliverability of WMD.” He goes on to quote an academic paper published in Biosecurity and Bioterrorism which states ‘this technology is gradually moving into the market place... [This] will soon put highly capable tools in the hands of both professionals and amateurs worldwide.’ Market states have come about by increasing globalisation, and technological improvements — and terrorists in those contexts can utilise that same progress. Take biological weapons as an example:

The DNA sequence of smallpox, as well as other potentially dangerous pathogens such as poliovirus and 1918 flu are freely available in online public databases. So to build a virus from scratch, a terrorist would simply order consecutive lengths of DNA along the sequence and glue them together in the correct order. This is beyond the skills and equipment of the kitchen chemist, but could be achieved by a well-funded terrorist with access to a basic lab and PhD-level personnel.

It will become easier to for both states and non-state actors to obtain these weapons. Just consider this non-exhaustive list from Salama and Hansell (2005):

British police arrested three men who were planning to use cyanide to attack the London Underground in 2002.

US troops in Iraq found 3kg of cyanide at the home of an Al Qaeda affiliate in 2004.

Russian scientists were helping Al Qaeda with the weaponisation of anthrax in 2001.

Multiple residences in Afghanistan, including the current head of Al Qaeda', al-Zawahiri, tested positive for anthrax

Midhat Mursi (an al-Qeda affiliate) constructed a radiological dispersal device.

In 2004, British police arrested 8 people who had been planning an attack on the New York Stock Exchange with chemical and radiological materials.

German police arrested an individual in 2002 for attempting to purchase 48 grams of uranium.

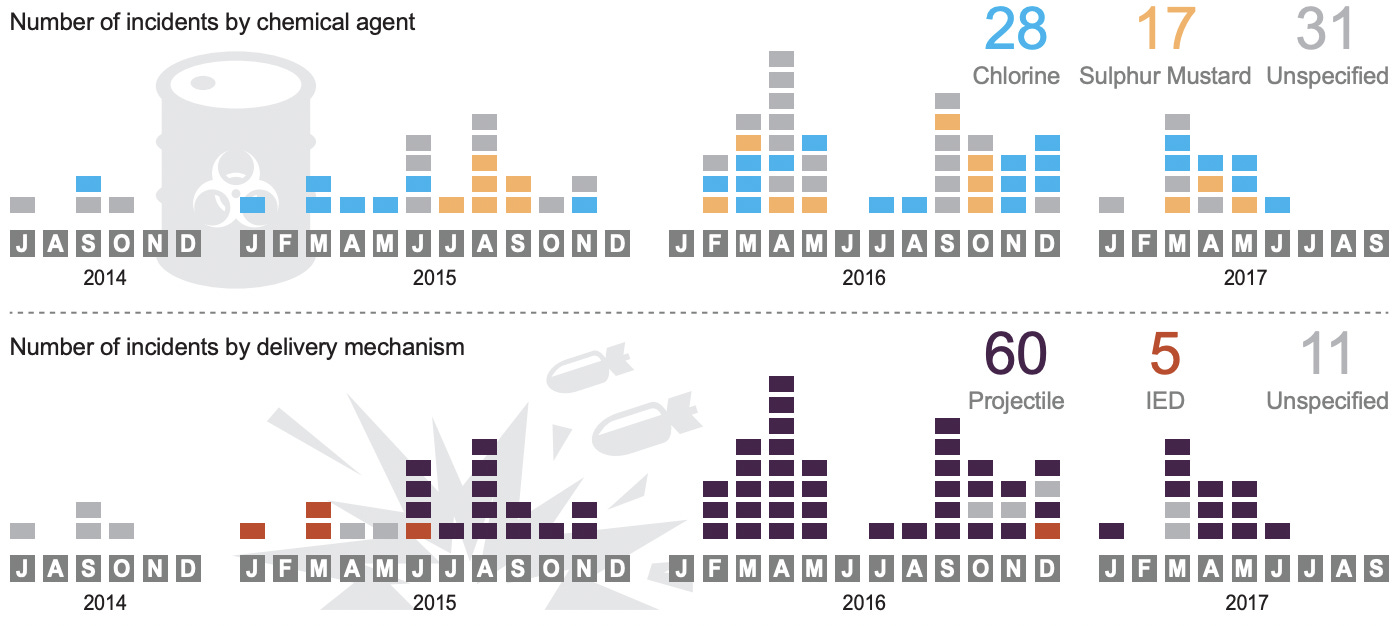

Much has happened since 2005 - indeed, both ISIS and Al Qaeda have used chemical weapons in their barbarous activities in Syria. Consider this illuminating report from Columb Strack which shows the trend of chemical weapons attacks by ISIS:

In the last three years, the Islamic State carried out attacks using chemicals on at least 76 occasions

Where, then, does Saddam come into play? In two ways. First, is that Saddam could give weapons directly to terrorists. It is superficially appealing to say that an (initially secular) Baathist regime would have no interest in working with Islamist terrorists - but we know that simply is not true. For a start, his aversion to Islamism is overstated. (Relatedly, many of those involved in ISIS’ chemical weapons production were involved in Saddam’s chemical weapons programme in the 1980s) Notwithstanding there was no operational link to Al Qaeda or any connection between Saddam an 9/11, it is clear that Saddam used terrorism for his own ends. In a review of 600,000 Saddam-era regime documents, Saddam’s use of, and funding to terrorist groups across the globe became bear. The conclusion of the authors is as follows:

…. while these documents do not reveal direct coordination and assistance between the Saddam regime and the al Qaeda network, they do indicate that Saddam was willing to use, albeit cautiously, operatives affiliated with al Qaeda as long as Saddam could have these terrorist–operatives monitored closely ... This created both the appearance of and, in some ways, a 'de facto' link between the organizations. At times, these organizations would work together in pursuit of shared goals but still maintain their autonomy and independence because of innate caution and mutual distrust

A rebuttal to this is that “why would a rogue state give a terrorist a weapon given the certainty that the source will be established?”. The simple answer is that we have an episode of a tangled web of such weapons being proliferated unchallenged - originating in Pakistan, an ally no less! - that severely weakens this argument. AQ Khan, a nuclear scientist, and his escapades are set out by Bobbit:

By the late 1980s Khan had established a relationship with Iran that led to the transfer of large amounts of nuclear technology, including the process for casting uranium metal. In 1987, three Iranian officials are said to have met several members of Khan’s network in Dubai. Khan’s intermediaries presented a program for Iranian nuclear weapons development….IAEA officials believe that Iran also received a complete design for a nuclear warhead from the Khan network…

KRL [Khan Research Lab] centrifuge technology found its way to North Korea….

…But, perhaps most significantly, he would create his own global commercial enterprise, establishing factories in third-party states to evade the export restrictions that were increasingly hampering his suppliers…

In 2001, Libya received 1.87 tons of uranium hexafluoride, flown in from Pakistan on an aircraft controlled by Khan. Later that year the Libyans were given validated—which is to say “tested”—nuclear weapons designs, accompanied by blueprints, sketches, instruction manuals, and other materials….

From 1976 to 2004, AQ Khan was able to operate a network which supplied sufficient knowledge and materials to construct nuclear weapons. That it took so long to stop him should shake our confidence in the idea that rogue states wouldn’t chance providing nuclear materials to terrorist groups. Indeed, consider the sheer amount of smuggling that goes on in this context:

The Illicit Trafficking Database of the International Atomic Energy Agency has reported… some 540 confirmed incidents of illegal commerce in nuclear and other radioactive materials between January 1, 1993, and December 31, 2003 (Bobbit, p.200)

I am by no means convinced in light of this history that states would not attempt to provide illicit materials or know-how because of the vague argument that no rational state would risk being caught. In any event, left to his own devices, Saddam could have produced sufficiently developed WMDs for his own use in countries across the globe. This is admittedly much more speculative, and a longer term possibility, but consider that Saddam-era documents revealed that the regime had the following materials held in embassies across the world:

Some may be unconvinced by the idea of Saddam giving terrorists WMD, or using WMD from embassies, as low probability events. But that doesn’t lessen the threat and the best way to explain why is through the legal case of Wagon Mound (No. 2) [1967] 1 AC 617. In that case, engineers were careless in taking furnace oil aboard in the Sydney Harbour. So careless that oil leaked into the water and drifted to a wharf where it was set alight accidentally. One of the relevant questions for the Privy Council was whether, despite there being a small risk of the oil catching fire, the engineers had a duty to prevent against it. I believe their Lordships came to the right decision. Lord Reid held

... it does not follow that, no matter what the circumstances may be, it is justifiable to neglect a risk of such a small magnitude. A reasonable man would only neglect such a risk if he had some valid reason for doing so, e.g., that it would involve considerable expense to eliminate the risk. He would weigh the risk against the difficulty of eliminating it... The most that can be said to justify inaction is that he would have known that this could only happen in very exceptional circumstances. But that does not mean that a reasonable man would dismiss such a risk from his mind...

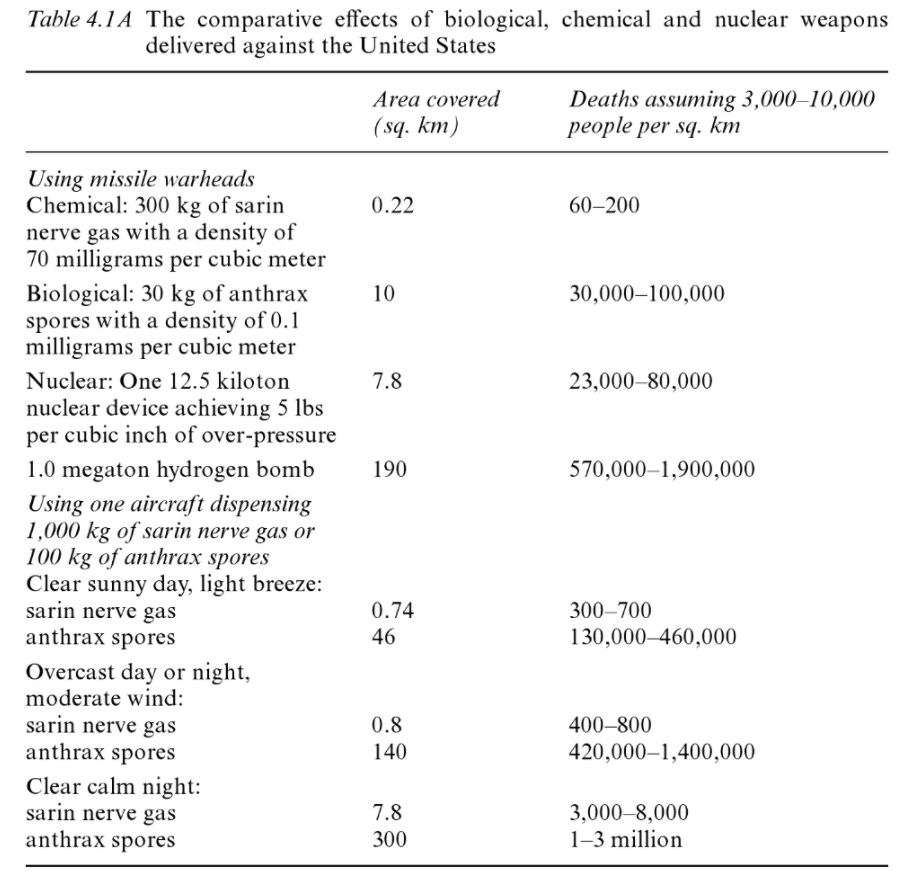

The production of chemical, biological and nuclear weapons in the hands of terrorists is not inevitable, or hurdle-free but low-probability, high impact events matter and the impacts here - as shown in the table below from Katona et al (2006) - undoubtedly warrant direct action, including the pre-emptive use of force.

Second, WMD proliferation should not be seen in isolation. Iraq was hostile to virtually all of the GCC states which surround it. The acquisition of nuclear weapons would likely lead to further nuclear proliferation - in much the same way that Saudi Arabia has said that it will acquire nuclear weapons if Iran seeks nuclear weapons. The instability of regimes in the Middle East, and the increasing terror networks would mean that nuclear proliferation across the Middle East would be the most significant security risk to the West, comparable to China and vastly surpassing Russia.

Violence against his own people

It’s worth listing out the destruction he caused to his own people. Let’s ignore the 1 million who died in the Iran-Iraq War, and let’s ignore the 75,000 killed as a result of his aggression against Kuwait. In 1988, his campaign against the Kurds destroyed 4,000 (out of 4,600) Kurdish villages culminating in 100,000 Kurds in their graves. (Incidentally, when Ali Hasan al-Majid, Saddam’s Defence Minister, was confronted by the Pershmega’s claim that 182,000 Kurds perished, he is said to have objected that it could not have been more 100,000). In 1991, Saddam’s reprisals against the Shia population exterminated well in excess of 100,000. A similar number of political killings occurred against a further 100,000 innocents though some numbers are as high as a million.

Unrelated to holding WMDs, Saddam’s almost Jong-ist impact on Iraqi well being is catastrophic. Iraq’s real GDP per capita nose dived from around $9,000 in 1979 to $1,000-1,200 in 2001 - of course sanctions were key in this, but the sanctions themselves were caused by a continuing and undisputed breach of requirements set by the UN Security Council (note here too UNSC Resolution 1441 affirmed a material breach of Saddam’s obligations). Here is how Davis et al (2006) summarise what Saddam did with the financial resources they had:

Much of Iraq’s greatly diminished output was diverted to an oversized military, an apparatus of terror and repression and the relentless glorification of Saddam Hussein. Pre-war Iraq employed nearly 500,000 persons in various intelligence, security and police organizations and a total of nearly 1.3 million when the armed forces and paramilitary units are included. All together, the various security organizations and military units accounted for about one quarter of employment in pre-war Iraq..

As they go on to note, Saddam expended about $2.5billion a year on monuments and mansions for himself. Davis et al (2006) set out that Saddam’s regime and these policies led to the loss of 200,000 lives prematurely. What all these numbers ignore is the intense torture of Iraqis from the gouging out the eyes of children to elicit family confessions, using acid vats to torture, and the systematic rape of women. Even this conceals the more mundane cruelty of the regime: from Uday Hussein torturing members of the Iraqi national football team and making them play with concrete footballs to the fact that Lisa Blayde’s brilliant State of Repression has a table entitled “TABLE 10.1. The number of draft dodgers and deserters arrested by area and the number of these individuals who had an ear cut off, from a report dated January 1995” - that such a table is necessary in a scholarly work is a testament to the depravity of the regime, and what he would have continued to do.