Summary

Crime is concentrated amongst a relative few rotten apples. We need a theory of criminal punishment that acknowledges that.

The empirical literature does not support the idea that longer sentences deter individuals from crime (i.e., stopping an individual criminal offender from re-offending) or deter at the population level (i.e., stopping non-criminals across the population from offending) at sufficiently adequate levels.

Incapacitation (i.e., preventing offenders from committing further crimes) does fit with the concentration of crime and is supported by the empirical literature. Tens of thousands of crimes could be prevented through longer sentences.

We should direct our ire to Government, not the courts, in failing to make provision for longer sentences.

A few bad apples

The starting point for any discussion relating to criminal justice should start with the concentration of crime. With thanks to Rosser et al (2017), here are some findings about how concentrated crime is:

Sherman et al.’s (1989) finding that in Minneapolis, 50 % of calls for service originated from 3.3 % of the cities addresses or intersections

Budd’s (2001) finding that 1 % of households in the UK experienced 42 % of residential burglaries

Bowers’ (2014) finding that 80 % of thefts in bars in London occurred in 20 % of facilities

Braga et al. (2011) show that 50 % of street robberies in Boston occurred on 1 % of segments.

Andresen and Malleson (2011) report that 50 % of vehicle thefts occur on 5 % of segments in Vancouver.

Weisburd's (2015) finding that between 0.4 and 1.6 % of street segments accounted for 25 % of criminal incidents in data for a number of cities in the US and Israel.

And so on - indeed, in a systematic review of the literature looking at the concentration of crime, across 44 studies, Lee et al (2017) find that the top 10% of serious crime places accounts for 63% of crime. It’s for this reason that I do not think emphasising policies which target deterrence or sanction at the wider, population-level are appropriate. (It’s also why I think those who argue there are entire no-go towns or cities where people should actually be in fear, are over-egging the pudding.)

There is some evidence for deterrence at an individual level (in contradistinction to a population-level):

In California, Proposition 8 required increased sentences for repeat offenders in cases of homicide, rape, robbery, aggravated assault with a firearm, and burglary. Kessler and Levitt (1996) find that within 3 years of Proposition 8, crimes covered by the law fell an estimated 8%. 7 years after the law changed, these crimes were down 20%.

Helland and Tabarrok (2007) look at the ‘Three Strike’ policy and in particular those who almost had two strikes as compared to those who actually had two strikes. They find that a 10% increase in sentencing reduced crime 1.2% and that people living in the shadow of a third strike were arrested 15% less per year.

Abrams (2012) finds that longer sentences for gun-related (or gun-aggravated) offences in the U.S led to an almost 18% reduction in such crimes three years after enactment.

Deterrence on an individual level is heavily confounded by the the incapacitation of the same individuals, particularly during their younger years when self-control is low and impulsivity is high. In any event, I just don’t think the bulk of the literature supports the idea that longer sentences would deter criminals or the population generally from crime. Re-offending rates are high notwithstanding they are somewhat reduced by longer sentences: in Britain, re-offending rates amongst Black offenders was 32.7%, Whites 30.6% and other ethnic groups approximately 20%. These are extraordinarily high numbers particularly in the context of crime being highly concentrated.

Doob and Webster (2003) in a literature review conclude that evidence does not support the idea that more severe sentences have a deterrent effect on an individual or general (population-level) basis. In a recent meta-analysis of 116 studies, Petrich et al (2021) conclude that “custodial sanctions have no effect on reoffending or slightly increase it when compared with the effects of noncustodial sanctions such as probation”. Importantly, Petrich et al make clear that imprisonment can be justified on the grounds of incapacitation notwithstanding this finding. Taking people out of action, particularly during their younger years, so they are incapable of inflicting harm on communities is where we should focus our attention.

Incapacitation, incapacitation and incapacitation

Thomas Mathiesen Prison on Trial famously concludes that incarceration does not “rehabilitate, deter or incapacitate”. I’m with him on the first, ambivalent about the second, and against him on the third. Here’s why.

In 2012, Siddhartha Bandyopadhyay, a professor from the University of Birmingham made a series of requests under the Freedom of Information Act to 43 police forces, covering the period between 1992 and 2008. Utilising public information to come up with an average sentence, in combination with this sleuthed information, he was able to find the impact of the length of incarceration on local crime rates. He found:

increasing the average sentence length for burglaries from 15.4 to 16.4 months would reduce burglaries in the subsequent year by 4,800; and

increasing sentences from 9.7 to 10.7 months for would result in a reduction of 4,700 offences a year.

Given the total number of annual burglaries was 962,700 and annual fraud offences was 242,400, a mere 1 month increase sentences is clearly not a panacea. But Bandyopadhyay found something else that was interesting: if, instead of automatically releasing prisoners at the half way point, we made them serve two-thirds of their sentences, burglaries would drop by 21,000, robberies by 2,600 and fraud by 11,000. That is a much more significant, and gives an indication that longer sentences work in reducing crime.

Buonanno and Raphael (2013) look at crimes following the period of ‘collective pardon’ for prisoners in Italy. Yes, they really thought it was a good idea to release one third of their prison population en masse. Buonanno and Raphael’s most conservative regressions estimate that the mass release increased reported crime by 57 per 100,000 residents per month. Following this increase in crime, Italian prisons inevitably started to fill up again. Buonanno and Raphael are able to estimate an incapacitation of 46.8 reported crimes per person-year at the six-month mark, and find an annualised incapacitation effect of 13 crimes per 100,000 for theft/receiving stolen property and 0.63 crimes per 100,000 for robbery.

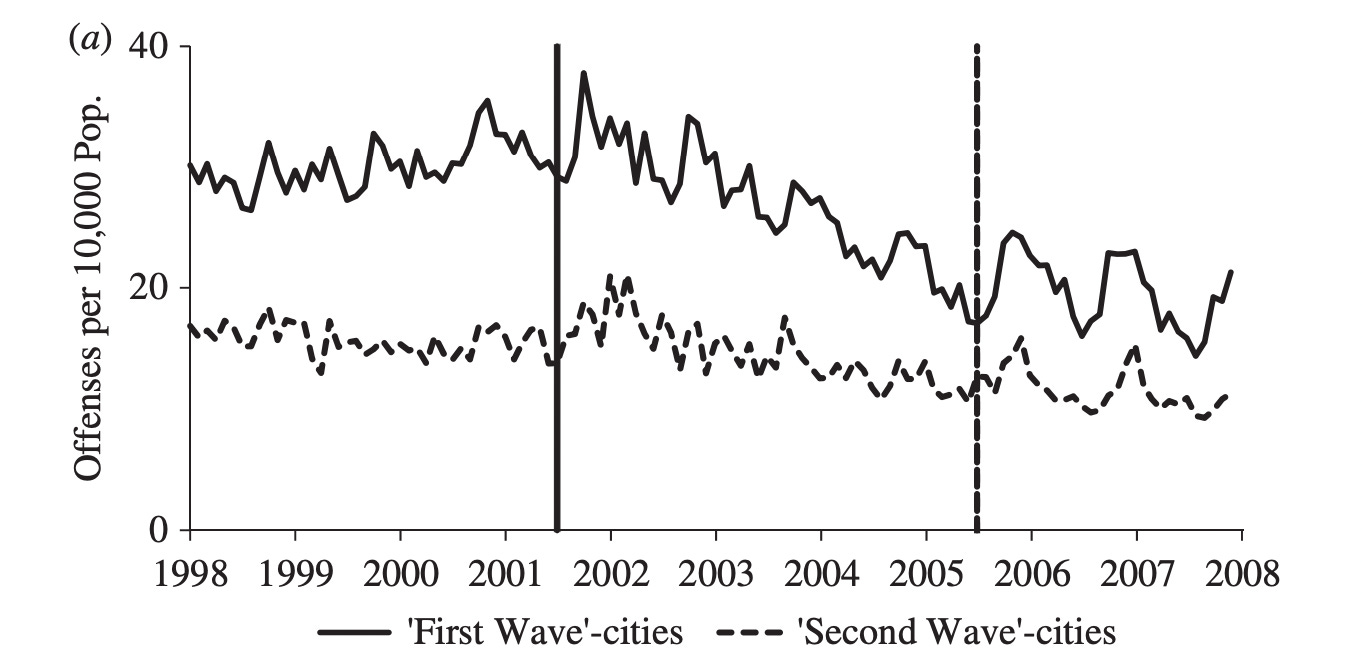

On the other side of the policy spectrum, in 2001 the Netherlands introduced for 10 regions (and then nationally in 2004) the ability for judges to impose ‘enhanced’ sentences for prolific offenders. Ben Vollard (2013) finds before the reform went into effect in the 10 regions, they had about 50% more crime than the 21 regions which had the reform introduced in 2004. Following the reform, crime fell in both groups, but faster in the 2001 cohort of regions. Overall, the reform led to a 25% drop in thefts.

Levitt’s (1996) study is another useful example of incapacitation effects. The widely discussed study focuses on litigation from the ACLU and other to close over-crowded prisons, using such litigation as independent variables. His findings are that a one-prisoner reduction is associated with an increase of fifteen crimes per year. 10 years after this study, Roodman (2017) replicated the results finding that “Levitt’s suggestion that increased incarceration reduced crime in the short run is plausible and is generally corroborated by the regressions and tests run here.” Amusingly, Vox - referencing Roodman’s work - ran an article entitled “A massive review of the evidence shows letting people out of prison doesn’t increase crime”. A curious headline given Roodman’s actual findings (which include the conclusion that all the incapacitation-studies he looks support incapacitation effects).

Emily Owens (2009) also considers incapacitation and looks at Maryland in the U.S. She specifically looked at a change whereby juvenile criminal records were no longer considered in sentencing. In effect, having been a juvenile offender approximately doubled time served for non-serious offences before, but not after, the reform. She found in this period of 'sentence disenhancement', the offenders committed 2.8 criminal acts and were involved in 1.4-1.6 serious crimes. Owens concludes that the social benefit of crimes averted by incapacitation is higher than the marginal cost of imposing a longer sentence.

There is also an indirect impact here: Billings and Schnepel (2021) find that peer effects also matter here. In particular, when offenders are released but their peers remain in prison, the offender is less likely to reoffend. They find that one additional peer incarcerated at the time of release decreases the probability of arrest (incarceration) by 2.4 (1.9) percentage points within the first year post-release. For more narrow definitions of peers such as family members and former criminal partners, their findings suggest a more than 10 percentage point decrease in the probability of recidivism. The mechanism is allowing the offender to return and integrate into society without bad influences or criminal incentives.

You’ll recall we mentioned Doob and Webster (2003) above - they are critical of a lot of deterrence studies because there is no attempt to separate out incapacitation effects which they find more plausible. As the evidence above shows, they have good reason to believe that incapacitation is more efficacious. It is worth noting in this context that the conclusion that harsher sentences are good at incapacitating is compatible with the view that too many people are in prisons, and that there is in a limited number of cases a budgetary offset for longer sentences.

The irrelevance of courtroom drama

Every time there is an outrageously low sentence handed down, there is an exchange of strawman arguments. “Legal Twitter” is alleged to say that unless you were in the room, you cannot comment on the appropriateness of the sentence. Very rarely is that the case, and often the argument being made (that the sentence is in line with the sentencing guidelines) is fair given that attacks are launched on the courts as though they are exercising discretion, rather than acknowledging they are following a statutory regime for sentencing. Squashing the authoritarian-lite angst against court should be an overriding concern.

For my part, I support longer sentences because I think the incapacitation effect is real and significant. I do not think the state should expend tax payer funds out of a sense of revenge or “punishment”, but it should concern itself with public safety. I don’t think the case for longer sentences is a slam dunk, but I think its the better argument and one which the public, rather than offenders, should bear the brunt of. This does not excuse the attacks on the court system: it is Government, and more specifically the Treasury, which prevents the approach advocated here.

Instead of spending our time on accusing Twitter QCs of being “pro-crime”, we should look at the real culprit: a Government that fails to legislate for longer sentences (e.g. the Government ended automatic release of terrorists at the half way point, replacing it with release at the two-thirds point), a government that refuses to reverse police funding cuts (police numbers by FTE in 2008-2012 were consistently above 140; in 2020 it was 129 and we have not even reversed the loss in 2010-11), and a government that slashes funding for the operation of the criminal justice system (see my previous post on the CPS).

Just consider the following:

A report last week by Her Majesty’s justice chief inspectors described “unprecedented and very serious court backlogs”. In crown courts, where the most serious criminal allegations are tried, this backlog now stands at more than 53,000 cases, contributing, the report said, to “lengthy waits” at all stages of the criminal justice process that “benefit no one and risk damage to many”.

It would, however, be wrong to assume, as the government insists, that these delays are solely the product of an unprecedented pandemic. The criminal justice system was already in a uniquely vulnerable position, with backlogs and delay a government-designed feature, not a bug.

Given the empirical record above, how many crimes are being committed by those who would have been incapacitated if the system worked as it should? Given this record, how perverse and pathetic is it that ire is directed at courts, and not the Government?