I was never a fan of this government. Even though I considered it preferable to a Corbyn-led government, I did not think it was right in December 2019 to conflate the celebration of the old codger’s deserved demise, with the celebration of a party that wanted to pursue (and has now actually pursued):

anti-state aid policies with the sole aim of wanting further intervention in the economy (1), including risking a calamitous no deal for that purpose (1);

the acceleration of irrelevant culture wars, in lieu of seriously increasing criminal sentences and ensuring funding which would enable the efficient operation of the criminal justice system (1, 2, 3, 4); and

undermining the judiciary, and the rule of law more generally (1, 2, 3) despite its own independent report showing there is no systemic issue with judicial review.

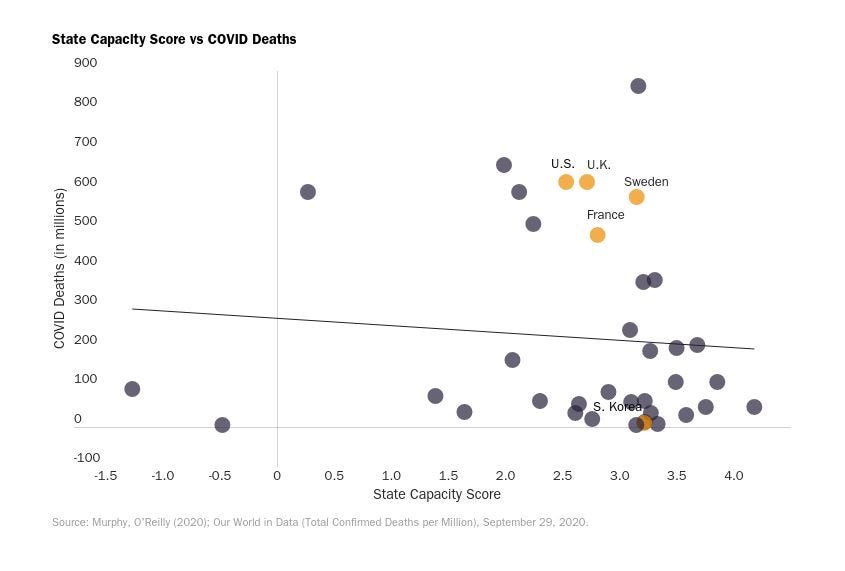

Given this track record, and assuming government competence correlates with good outcomes and vice versa, how the UK has handled the coronavirus pandemic shouldn’t really be surprising: we have over 150,000 dead, including one of the highest excess death rates across Europe. It doesn’t look like normal measures of state capacity are helpful in predicting the UK’s dismal outcomes, as Ryan Bourne points out:

So what is driving it? There is a narrative that pins this not on the decision makers (i.e., government), but the people advising the decision makers. This type of thinking - buoyed by those with an almost manic obsession with the civil service, the “Blob” and “officialdom” - indirectly shifts culpability onto the advisers, away from our populist government. I think there should be a presumption against this argument for the obvious reason that advisers don’t carry decision making power. Indeed, ministers have explicitly said as much in this very context.

Before explaining why its wrong beyond just a presumption, there are, however, two grains of truth in this line of thought worth noting:

SAGE got an awful lot wrong: it did not explicitly call for lockdown when it should have in early March 2020; they got it wrong on border closures; they got it wrong on masks in the early part of last year; they got it wrong on large public events; they did not emphasise ventilation; and they have generally understated the impact of schools in transmission. Particular officials like Patrick Valance have adopted the herd immunity approach, a policy that would have been an unmitigated disaster and costs us even more lives.

The less “macro” the decision, the more reliance which should be placed on advisers given the information asymmetry. So, for example, I am less willing to place the blame on ministers for not emphasising ventilation in the very early months of 2020.

But a line of thought that emphasises officialdom, rather than ministerial competence, as the cause of our horrendous performance seems fundamentally wrong to me for the following reasons.

First, even where an explicit recommendation is not made (or indeed, a contrary recommendation was made), the question is whether the relevant information on which to reach the correct decision had been provided. My own view in reviewing the papers produced by Neil Fergusson, John Edmunds in late February / early March (which showed at least 270,000 people dying under the government’s strategy), as well as the under-appreciated paper by Steven Riley prepared in early March alone should have warranted early action. That latter paper explicitly signposted to the strategy being pursued in South Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong. It’s worth noting that Dominic Cumming’s (delayed) support for lockdown reportedly came about because of the information from SAGE.

Second, again even where an explicit recommendation is not made (or indeed, a contrary recommendation was made), a decision has to be seen in the context of how reasonable it is. The age old telling off “if your friend told you to jump off a cliff, would you have done that?” is relevant here: by early March, it was unreasonable to listen to advisors even if they had been saying that lockdown wasn’t necessary, such that culpability for that decision should reside with the government.

In this regard, SAGE and SPI-M papers were not the only source of information: I was radicalised into supporting lockdown early on by my friend Saloni Dattani, but even those who aren’t lucky enough to have Saloni as a friend could have read her case for lockdown; or the early case by Tomas Pueyo, or articles in mainstream publications - cases which it really wouldn’t be difficult for a minister to come by. This really wasn’t a hidden secret: how East Asian countries were acting was readily available to see, and even Europe started imposing restrictions well in advance of us with Boris nodding along as he was told they were pursuing such strategies for political ends.

Third, and most importantly, we can ask what would have happened if SAGE and the government’s advisors had got it right because, as time went on, they did start to get things right - and we can see they were roundly ignored:

The early re-opening following the first lockdown in May 2020, with SPI-M advising that the government’s actions would lead to an increase in R (see here).

SAGE called for a circuit breaker lockdown in September 2020 - again, completely ignored (see here).

SAGE recommended moving to online learning for colleges and universities - something which was again ignored (see here).

The same goes for the 10pm curfew that was imposed on the latter half of last year (see here).

In October 2020, SAGE suggested that bars and restaurants should be considered for immediate closure - something which was roundly ignored (see here).

Government advisors were against the operation of the Tier system (see here)

The warnings over the Christmas 2020 strategy were ignored before a reversal 3 days before Christmas Day (see here).

SAGE said in December 2020 that schools should not be opened in January 2021 - the government decided to let every child go to school for one day, and then shut them down (see here).

SAGE warned that the government’s half assed quarantine strategy would lead to the easy entry of variants in the country (see here).

The opening of schools in March 2021 was against the advice of government advisors (see here).

This shouldn’t be surprising: this government has made a habit of ignoring its advisors on fairly big decisions like Brexit, and judicial review, right down to the granularity of ignoring its advisers on highways policy, local town investment decisions, tech policy, and even redecorating Number 10. Indeed, even the PM’s closest political advisor wanting a lockdown in September was roundly ignored.

What the reports of decision making show is that ministers considered the advice, but then wrongly considered political and economics considerations took precedence: for example, incorrect views about the economic and social impacts of lockdown was the cause of dither and delay in mid-March (see here, here) - a delay that cost at the very least 20,000 lives (see here). The decision not to have a lockdown in September was driven by the incorrect economic considerations of Rishi Sunak (see here). More recently, the government’s delayed imposition of quarantine restrictions on India is reportedly related to cosying up to Modi.

One useful little anecdote that is representative of this consistent pattern of behaviour relates to Boris Johnson, now infamously, saying that he was continuing to shake hands with people in March 2020. On that very day, SPI-M had released a paper stating that government should advise against shaking hands. Of course, we can now be less concerned about this kind of transmission; but the point is that the government has consistently ignored the advice of its advisors: emphasising the mistakes of these advisors fails to appreciate the actual decision making process, and the actual rationale for the decisions made.

Fourth, particularly as time went on, the selection of advisors became exogenous to the government’s own competence, and political preferences. In September 2020, the government invited four academics: Gupta (who claimed 50% of the UK may have had COVID in March 2020), Heneghan (who claimed Covid was “waning fast” in 2020), Tegnell (the butcher of Sweden) and, the sole pro-lockdown representative, John Edmunds (who argued, consistent with SAGE’s advice, that “not acting now to reduce cases will result in a very large epidemic with catastrophic consequences in terms of direct Covid-related deaths”). The point, therefore, is that the government started to select advisors that supported an anti-lockdown mantra.

What does all this mean? If state capacity is not predictive, and if what advisors say doesn’t seem related to government action, what is? I made up a concept of “statesman capacity” (another way of saying governmental capacity) which seems relevant here. Going back to the policies at the very start of this post that the Tories have now adopted, it’s noteworthy that these are not well supported by the median competent member of the elite (indeed, this government made a show of expelling the sensibles amongst them). This could be, for example, because the kind of ideas supported by the government attract incompetent people or these ideas are correlated because they both stem from ignoring “experts”; or it could be that these damaging policies were really just a shibboleth for some intra-elite competition.

Whatever the reason, in light of this level of shunning advisors, I find it difficult to stomach the idea that ministerial competence isn’t the predominant cause of our woes. The idea that all that stopped us locking down on March 1 was SAGE is wrong. It seems plain to me that individuals like Rory Stewart or Jeremy Hunt (who “got” coronavirus much much earlier than Boris “the best thing to do would be to ignore it” Johnson) undoubtedly would have have higher “statesmen capacity”, and would have acted earlier. That conclusion is inconsistent with overstating the importance of SAGE, and other advisors / officials.

But what about the vaccine rollout?

The UK has carried out a remarkable vaccine rollout: we were the first in the world to approve vaccines, and leaving aside Israel and Bhutan, are leading the pack. Does this not suggest that the concept of “statesmen capacity” is proving too much? I don’t think so for two key reasons:

It seems clear that the private vaccine production, MHRA approval, and NHS roll out itself has been relatively detached from ministers. Indeed, the Times reported that most of roll out strategy was in place long before there was a ministerial appointment.

Brexit.

On the second, it’s worth elaborating: the regulations that were used to approve vaccines, and opt out of the combined European programme, were in place long before Brexit, when we remained members of the EU. When Brexiteers discovered this, they came up with a new argument that “pressure” would have caused the UK to take part. That argument lost force too when European countries started to diverge from the European programme mere weeks into it (even ignoring the dubious suggestion that the UK would have acted like other European countries). Then came the argument the UK would not have diverged because of the presence of the European Medicines Agency in London. Except, that doesn’t quite make sense either: a Freedom of Information Act response I obtained showed that the UK diverged from Europe on approvals like this 278 times between 2012 and 2019, even with the EMA firmly in London.

Plainly, given that history of divergence and the current actions of EU member states, Brexit was not necessary for divergence. But, relative to a number of scenarios (e.g., a Miliband government that avoided a referendum, or a Corbyn government), it made it more likely for this government to diverge. There are other plausible scenarios where Remain and vaccine divergence would have been possible (e.g., Cameron winning the referendum where following the EU too closely would have been scrutinised) or where it would have eventually happened (e.g., scenarios where ministerial competence is high) - hence my view that seeing this as a “Brexit boon” is a folly, particularly given the downsides it brings. Indeed, if you buy the idea of “statesman capacity” and accept that bad policies correlate, then Brexit is very likely to have been related to the lethal outcomes in the UK.